…tell the old story for our modern times. Find the beginning.

-Homer, The Odyssey (Emily Wilson translation)

When I first got the email notice of this concert, I was, to say the least, intrigued. A two piano concert at Littlefield Concert Hall on the campus of Mills College featuring two composer/performers who figured prominently in that Temple of new music and in my personal listening life. Alas, I live some 350 miles from that location. But further intrigue came from the featured artists: Sarah Cahill and Joseph Kubera, two of the finest working new music pianists anywhere and both worked with the evening’s composers. This was just too compelling and I decided that I would regret missing this if I failed to go hear it.

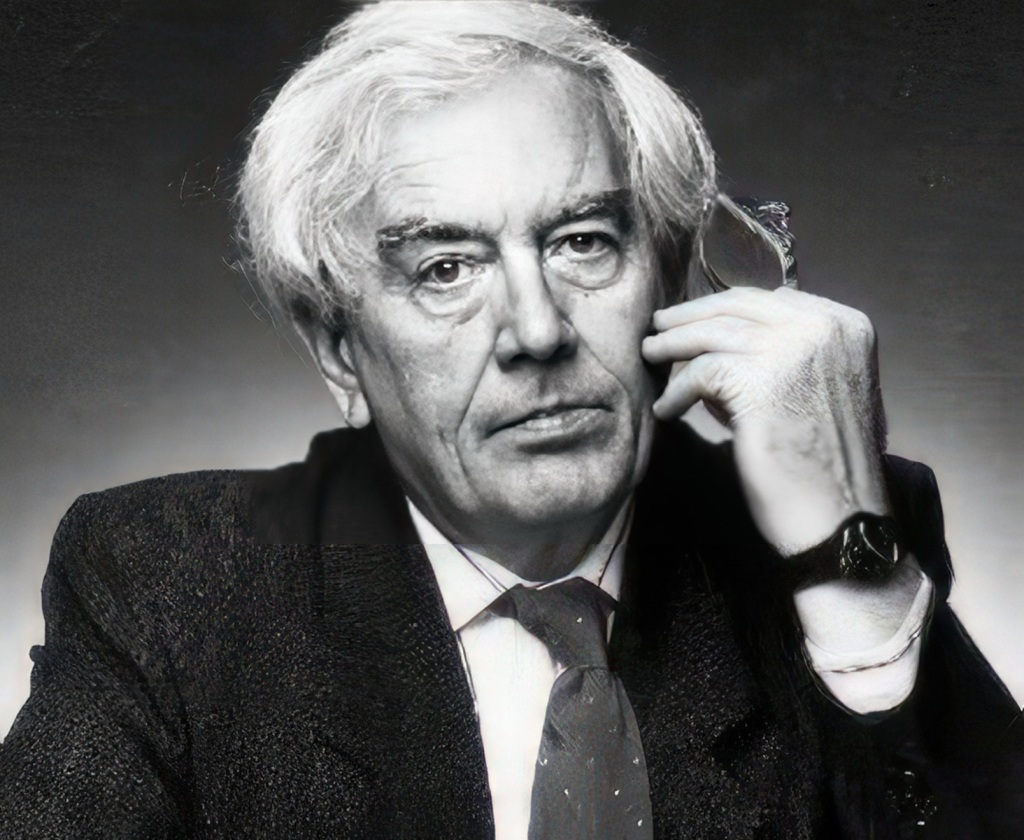

So it was, I planned my little odyssey, leaving at about 9AM from Santa Barbara on a nice lightly trafficked trip, more a pilgrimage than an odyssey. A pilgrimage, frequently defined as a personal spiritual journey ostensibly in search of insight or enlightenment is how I’ve come to identify my listener’s adventure to the secular temple of Mills College featuring music of former Mills faculty Robert Ashley (1930-2014) and Robert Sheff (1945-2020), better known by his stage name, “Blue Gene Tyrrany”.

The two featured composers had a strong connection to the Bay Area, mostly via their work at Mills College. This intelligent but modest production left little room to print program notes so the performers spoke of the music at various points during the concert and the excellent liner notes were made available by a QR code in the program book.

Our two performers are no strangers to each other or the composers on the program, having collaborated on numerous performances and recordings. The well rehearsed duo turned in riveting performances of this largely unknown repertoire which made a strong case that it be better known. Their playing and choice of repertoire compelled this listener’s attention such that I forgot to take all but a few performance shots. See those program notes for further biographical info on these two fine musical celebrants.

Mills College has long been a temple, a Mecca for new music in the Bay Area of California. Its roster of faculty and students comprises some of the finest post 1945 composers and performers. Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) and Luciano Berio (1925-2003) and students as diverse as Terry Riley (1935- ), Steve Reich (1936- ), and Dave Brubeck (1920-2012) to name but a few. Many artistic spirits musical and otherwise, exert their presence here. It’s a perfect destination for a pilgrimage.

The concert was organized by Charles Amirkhanian and his Other Minds organization, another guiding light in the San Francisco/Oakland new music scene. Pianists Sarah Cahill and Joseph Kubera were to be the celebrants in the concert ritual paying homage to “Bob and Blue” as well as to the oracular Mills College.

Let me tell you about this concert hall. It is the work of legendary California architect Julia Morgan (1872-1957) who famously also worked on Hearst Castle. This is one of her several architectural gems on campus. Her spirit was also witness to this celebration by virtue of her fine architecture.

Two pianos, a new Steinway stage left and a slightly worn Baldwin stage right were placed such that the pianists seated at their respective keyboards could see each other. The Steinway with its lid open to reflect the sound to the audience and that well worn Baldwin with no lid at all (for reasons to be revealed later). The sonics of the hall and tuning of those pianos were excellent.

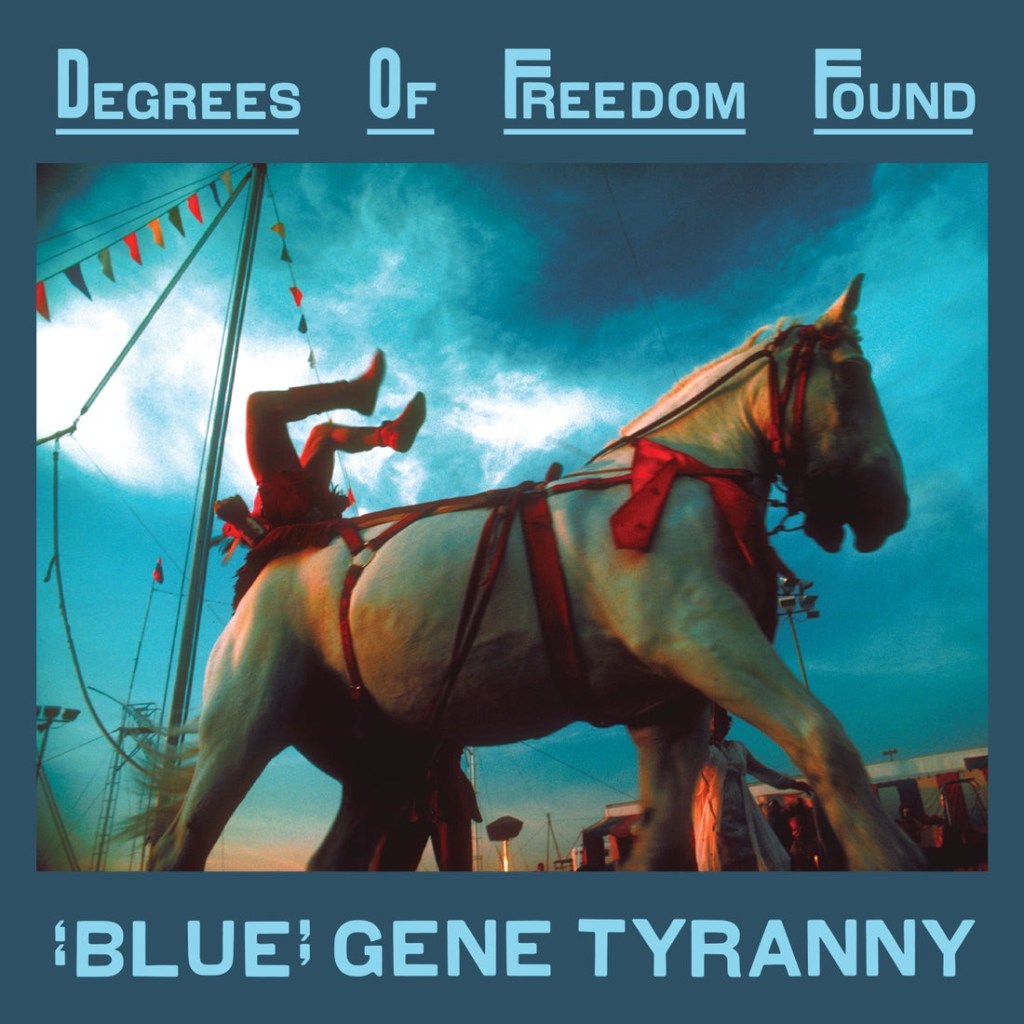

The concert opened with Blue Gene Tyrrany’s peaen to old Route 66 in his “Decertified Highway of Dreams” (1999) for two pianos. It was clear from this first selection, that our performers were well rehearsed and in sync despite rhythmic complexities inherent in this quite beautiful work. It is cinematic and sweetly nostalgic, a fine example of “Blue”’s genius. The performance was riveting and worthy as the first performance ritual of the evening.

This was followed by a real rarity, a performance of Robert Ashley’s Piano Sonata (1959, 1979, 1985). In fact, it appears to have been the first complete performance of the two piano version of this impressive serially structured piece. Previous recordings are available, one with the composer performing the first movement at the ONCE Festival from 1966, the other by Blue Gene Tyrrany on his album, “Just for the Record”. This writer also found some useful analysis by musicologist Kyle Gann on his website. Gann worked with Ashley and later published a fine survey of Ashley’s music that is well worth your time. The result was a convincing, almost romantic sounding performance of this foundational work in Ashley’s oeuvre.

This was followed by a solo rendition by Joe Kubera of Tyrrany’s “The Drifter” (1994), which was written for Mr. Kubera. He spoke briefly about the structure of this work (which he also recorded on his recent “Horizons” album). This piece has a meandering quality created by the intricate evolving structure. Kubera’s performance was hypnotic and a fine tribute.

The second half began with Ms. Cahill solo at that stage left Steinway playing first Tyranny’s “Nocturne With and Without Memory” (1989), one of his better known works. Then she played his “Spirit” (1996/2002), a piece that is a sort of homage to the experimental composer/performer Henry Cowell (1897-1965). It was rather unusual in that it involved harmonics over which the pianist plays. The title is an homage to Cowell’s famous piano piece, “The Banshee”, a malevolent spirit in Irish mythology. Both were vintage Blue Gene pieces.

Then Kubera returned, taking a seat at the blemished Baldwin with Cahill standing at that same piano, at a 90 degree angle to Kubera. Here, in these two obscure Ashley pieces, Viva’s Boy (1991), and “Details” (2b, 1962), Cahill played like a chef at a chef’s table, playing the strings inside the piano while Kubera manned the keyboard. These true rarities getting perhaps their first performance, were certainly a highlight of the concert.

It was Blue Gene Tyrrany’s spirit that was the final ritual celebration on this magical night with both pianists at their respective pianos to give a heartfelt reading of his, “A Letter From Home” (2002). This brought this learned, well rehearsed, beautifully collaborative evening’s ritual to a satisfying close.

The modest, self selected audience, applauded warmly and gave an extended, much deserved ovation and seemed as enthralled as this listener whose musico-spiritual pilgrimage found an ecstatic height. I drove home that same night, blessedly lifted, if only briefly, from the chaos of the world by this wonderful artistic ritual. They will now take this great program to New York.