“Fragment #3”

speaking is speakingWe repeat

what we speak

and then we are

speaking again and that

speaking is speaking.

TokyoJune sometime, 1976 Richard Brautigan (1935-1984)

(Left to right: Clark Coolidge, Karen Stackpole, Michael McClure, Anne Waldman, Randall Wong, Aram Saroyan, Sarah Cahill, Charles Amirkhanian, Carol Law, Alvin Curran, Beth Anderson, Jaap Blonk, Tone Åse, Amy X Neuberg, Sheila Davies Sumner, Enzo Minarelli, Ottar Ormstad, Susan Stone, Pamela Z, Taras Mashtalir)

The last statement in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s 1921 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent) is well known among philosophy students and has taken on the quality of an aphorism or truism. But the six days of this most recent Other Minds Festival was functionally an effective refutation of this concept. And the controversy over the awarding of the most recent Pulitzer Prize in music to a rap/hip-hop artist (a species of sound poetry?) which was announced on April 16th, 2 days after the end of this festival of sound poetry seems to reflect the prescience and presence of mind of the Other Minds organization. Apparently words are “in” even if Wittgenstein and the critics of the Pulitzer Foundation say otherwise.

The Wages of Syntax

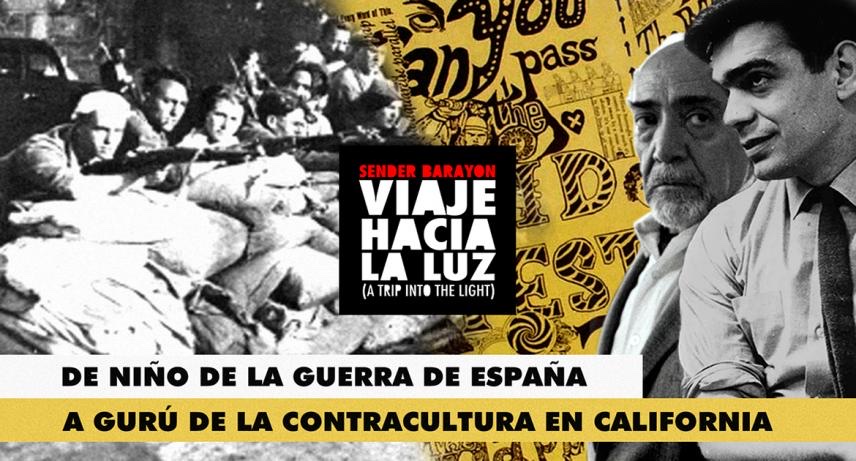

Other Minds 23 (April 9-14, 2018) in many ways began with the release in 1975, of one of the first (and still arguably the finest and still in print) anthologies of a strange, somewhat nebulous species of what can loosely be termed “sound poetry”. That anthology was called “10+2: 12 American Text Sound Pieces” curated by the man behind this week’s vast expansion on that anthology, Charles Amirkhanian.

Amirkhanian and his wife, artist and photographer Carol Law took a long strange trip in the early 1970s. No, they did not follow the Grateful Dead. Rather they sought a little known group of artists who walked a line seemingly between poetry and music. From the Nordic countries to northern Europe, France and Italy they encountered artists who used the voice (though not necessarily language per se) to produce a sonic art form which nearly defies categorization.

Amirkhanian in his office

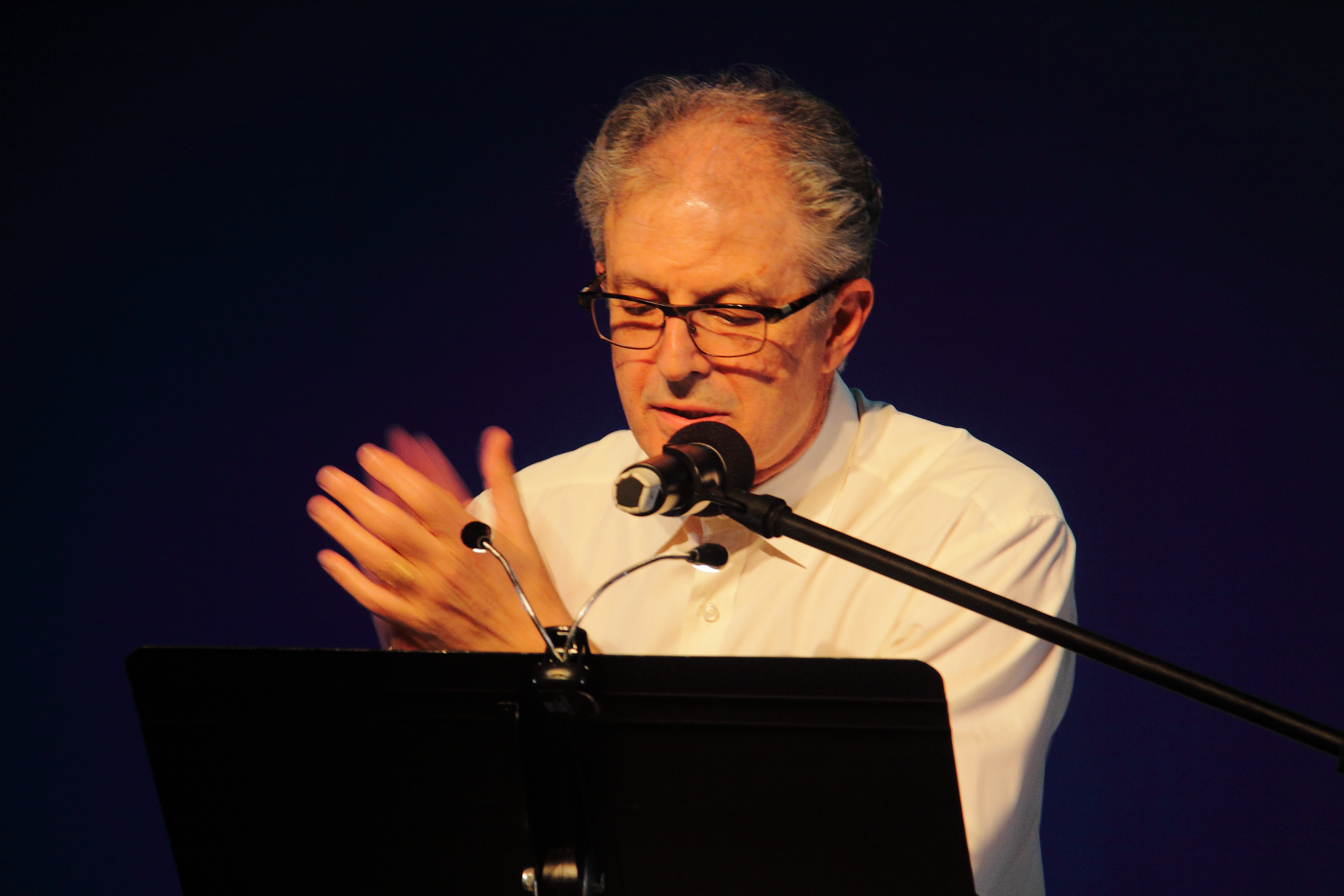

Charles Amirkhanian is himself a composer and percussionist in addition to being a producer and promoter of contemporary music. As a composer, as it was with his long radio career, his voice has been his main instrument. His resonant, articulate baritone voice has served him well these years and this festival provided a rare opportunity to see/hear Amirkhanian perform his own work live.

This unprecedented 6 day festival marks the longest in the series of the Other Minds annual music festivals. As relatively obscure as this art form may seem to the casual observer this series managed to provide historical context, current practices, and a tantalizing look/listen at the future of what is in fact a vast body of work. The ability of Other Minds to find hidden treasures of sonic art continues to amaze.

Day one,subtitled, “The Wages of Syntax”, was the gala opening featuring some of the leading artists in the field. After the obligatory intros the Italian master Enzo Minarelli presented the world premiere of his tribute to Stephane Mallarmé, “Ptyx”.

The piece, comprised of phonemes rather than syntactical sounds, was an apt introduction to the weird and wonderful world of sound poetry. Minarelli was passionate and expressive, a beautiful performance. Only later in this series would we come to know the depth of scholarship, preparation, and experience that informed this and all his performances. More on that a bit later.

Next up was one of the elder statesmen of San Francisco poets, the wonderful Michael McClure. At 85 he sported a walking stick (no not really a cane) needed due to a recent fall. He also required assistance of one of the stage managers to help him to the little chair and desk set up for him. But none of that mattered once he opened his little bookmarked book of poetry and began to read “Marilyn Monroe Thou Hast Passed the Dark Barrier” and some of his Ghost Tantras from 1962. His voice was strong, his delivery both certain and witty. His combinations of words and non-syntactical sounds were delivered with the same joy, humor, and pathos which appears to have inspired them in the first place. The audience responded very warmly to his ecstatic delivery.

After a bit of stage preparation we were treated to one of the most prominent members of the next generation of American poets that followed Mr. McClure (can I be forgiven for saying beat poets?), Anne Waldman. She was accompanied (as her texts required) by percussionist Karen Stackpole. Waldman presented from her “New and Selected Poems”, “Pieces of an Hour (for John Cage)”, excerpts from “Voices Daughter of a Heart Yet to Be Born”, and excerpts from “Trickster Feminism”. Her characteristically forceful and peripatetic performance carried her between the microphone and Stackpole’s percussion instruments and back again. It was a charged and sincere performance which clearly charmed (some might say stunned) the audience.

Waldman’s ties to the world of sound poetry go back to her New York roots and her involvement in the St. Mark’s Poetry Project and the Dial-a Poem Poets whose recordings have included her work and that of John Cage, Charles Amirkhanian, Clark Coolidge, and Michael McClure among others. Small world.

Next up was the venerable Aram Saroyan. I suppose Saroyan (yes, the son of Pulitzer Prize winner William Saroyan) can be said to be part of the same post beat generation artists as Waldman. Perhaps best known for his “minimalist poetry” he is also an accomplished biographer (Genesis Angels deserves to be better known IMHO) and literary innovator. It was Saroyan’s poem “Crickets” (1965) which ended the first side of that anthology mentioned at the beginning of this article. It was in an infinite loop in the end groove of side one of the LP playing the one word which comprises the poem, “crickets”. And it was this little gem that he performed on this night….with a twist. After a few repetitions he invited the audience (many apparently still trying to figure out what was going on) to join…which we did…,at first hesitantly, in unison…and then, in a touch of group inspiration, just like real crickets, not all in unison. It was a strange sort of call and response that charmed the audience and brought a smile to the poet as well. And that only brought us to intermission.

Michael McClure, Anne Waldman, and Aram Saroyan

The second half introduced the first of the international stars, Jaap Blonk, the Dutch sound poet and performance artist. He began with one of his own works, Obbele Boep ‘m Pam (a bebop sound poem). It was a sound poetry homage to that 1950s species of jazz which inspired the beats, Bebop. It was a sequence of sounds and words in a made up (by the performer) language intended to imitate the sound of his native Dutch language.

His second performance was of a sound poem from 1916 by the man who coined the term, “phonetic poem”, Hugo Ball (1886-1927). This poem, based on phonemes common to the Swiss and German languages, was called, “Seepferdchen und Flugfische” (in English “Seahorses and Flying Fish”). Blonk’s delivery of this turn of the century classic was the first of what would be several such revivals of revered early material of this nascent artistic genre.

Jaap Blonk

Blonk was followed by the grand finale which returned us to the local roots with poet Clark Coolidge and the ever innovative Alvin Curran. We learned that the two went to high school together and this was a strange and wonderful reunion with Coolidge reading his manic stream of consciousness poetry accompanied (sort of) by Curran’s musical ministering at both a grand piano and a sampling keyboard in a world premiere collaboration.

Though Curran now lives in Rome (and has for many years) he will always be welcome in the Bay Area where he lived, taught, and performed for many years. Curran is no stranger to Other Minds either having performed at Other Minds 7 in 2001 and, more recently, at the Nature of Music series. He is a musician, not a poet but his eclecticism has allowed him to collaborate successfully with a wide variety of artists in a long and varied career which continues to command attention.

The nature of the interactions which characterized this world premiere performance of “Just Out of Nowhere” were not obvious though it is a fair assumption that a degree of improvisation was used and, no doubt, some of the successful confluences on this night were first encountered in rehearsals. Coolidge’s stream of consciousness rhythmic ramblings were ever present but never overwhelming. In response, Curran moved back and forth between the grand piano and the sampling keyboard working with serious concentration to provide his musical support for the words.

It was an intense performance as inscrutably mind expanding as all that went before. Curran signaled the end (as has become his performance custom) by blowing the sacred shofar over the undampened piano strings which resonated in kind and faded to silence which, in turn, was held for a moment by the audience as they disengaged from their attention to offer warm and appreciative applause. It was a striking collaboration and a reunion of two beloved artists.

The audience seemed to feel the pure emotion of this performance and the two performers embraced warmly before acknowledging the accolades of the charmed audience.

Sadly this writer had to miss the second night of the festival which consisted of a lecture by Enzo Minarelli on the history of sound poetry followed in the evening by a workshop on how to do sound poetry run by Jaap Blonk. Both were apparently well received and it is my understanding that they will soon be available for streaming on the Other Minds web site. Definitely gonna check that out.

The second night was given the subtitle, “No Poets Don’t Own Words”. Even for those who were fortunate enough to have attended this extended Tuesday program it is worth noting that there is a wealth of resources easily available to the interested listener. The Other Minds website has links to a wealth of archives which include interviews and performances by a variety of artists. In fact (and this was a creative touch) you get a free CD entitled, “What is sound poetry?”, an archived KPFA radio program when you buy one of the unique t-shirts (designed by none other than Carol Law) from the Other Minds Web Store. Get this stuff while you can folks.

Also worthy of note (this writer has lost many hours browsing here) is Ubuweb, an online archive of music, texts, films, and sound poetry. The fact is that these six evenings ultimately could only serve as an introduction to the unusual and entertaining genre. And those whose appetites have been whetted by this series will want to hear more.

The History Channel

Day 3, April 11th. The subtitle for this night’s performance was, appropriately, The History Channel. It was an opportunity to display some of the origins and early foundational masterworks of sound poetry. Enzo Minarelli displayed his academic skills and interests as he interpreted several classic “scores” (which were projected on the back wall) as the performer brought them to life in what appears to have been as authentic a performance as could be had with this material from the early twentieth century.

Minarelli did readings of: “Dune (parole in libertå)” (1914) and “Zang Tumb Tuuum: Adrianopoli, 1912” (1914) by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti; Fortunato Depero’s “Subway” (1939), “Verbalizzazione astratta di signora” (1927), and “Graticieli” (Skyscrapers, 1929). He finished with one more by Marinetti, “Savoia” (1917). In addition to the passion of Minarelli’s performance the look of the score, essentially artistically printed pages of words and phonemes, and the choices made by the performer to interpret those scores itself provided its own sense of drama. The lighting and projection were simple and effective, supporting the live performance.

No major stage changes were needed for the next performer, just a little music stand with a microphone and small lights to illuminate the score. Randall Wong, currently administrative director at Other Minds is an accomplished singer. He is in fact a male soprano who specializes in baroque vocal scores including opera. No stranger to new music, Wong has also demonstrated his formidable vocal skills singing with the Meredith Monk Ensemble among others. It was those extended vocal skills that were called upon this night.

One could hardly have found a more appropriate casting to perform this next item on the program, “Stripsody” (1966) by the deservedly celebrated new music soprano Cathy Berberian. Similarly to Wong, Berberian’s career took her from baroque opera to a plethora of modern music (Berberian was married for a time to Italian modernist composer Luciano Berio who wrote many a score for her). What is lesser known is that Berberian wrote some music designed and inspired by her own vocal skills.

Stripsody is difficult to describe.

It is, in fact, a combination of sounds, specialized vocal utterances, and visual theater and is a sort of homage to comic strips (hence the title). Utilizing onomatopoetic sounds, imitations of real world sounds and the sheer range of Berberian’s vocal instrument the performer becomes a sort of live comic character. This piece is demanding but highly entertaining and contains humor and a variety of references. Never did the audience lose track of the virtuosity involved or the intensity of the performer’s stage presence. Wong’s performance was at once accurate, virtuosic, and a touching evocation of the memory of Ms. Berberian.

It was an immersive experience for both performer and audience witnessing the sounds, the gestures, the facial expressions, the sheer concentration required to convey both the humor and joy of this work. Wong demonstrated serious stamina and seemed to have enjoyed himself.

Now what is history without a bit of archaeology added in? Charles Amirkhanian introduced writer Lawrence Weschler who is (bear with me now) the grandson of the composer Ernst Toch. Toch is responsible for writing what is perhaps the best known example of the genre represented by OM 23 this year.

In 1930 he wrote a three part composition entitled, “Gesprochene Musik” (Spoken Music). Two of the three parts of this composition had long been thought lost. However choreographer Christopher Caines apparently did a reconstruction for his dance piece, Spoken Music (2006). Tonight’s performance was the American premiere of substantially what Toch had originally intended way back in 1930.

The last of the three pieces, “Geographical Fugue” is by far the best known of Toch’s spoken music (indeed the probably the best known of all his music despite a truly substantial catalog and a Pulitzer Prize, no less). In addition to the Gesprochene Musik there was a performance of a much later work by Toch which parodies chatter at cocktail parties, “Valse”(1962).

All of these were performed by The Other Minds Ensemble which consists of Kevin Baum, tenor; Randall Wong, tenor (yes, he can handle both soprano and tenor); Joel Chapman, baritone; Sidney Chen, bass, Amy X Neuberg, and Pamela Z.

Fast forward now to 2014 when grandson, executor, and writer Lawrence Weschler came up, on a whim, with a medical text to fit to the original Geographical Fugue. Tonight we were treated to the world premiere performance of Medical Fugue with the same ensemble. Weschler’s facility with language allowed him to choose the phonetics which worked as effectively as Toch did in his original. No doubt grandaddy would have been proud.

Following intermission Jaap Blonk again took the stage, this time doing a historical performance for which he has become quite well known. Tonight he performed (from memory, no less) “Ursonate” (1932) by Kurt Schwitters. This large and complex work in several sections (or movements) utilizes vocal sounds fit together in the manner of classical sonata form in music. Blonk has been performing this work for many years now and he obviously both knows and loves this piece. His sincere, kinetic performance brought the audience back to the time frame of those years between the wars most effectively.

Two pieces on tape were next: “La Poinçonneuse, Passe Partot No. 2” (1970) by Bernard Heidsieck (1928-2014) and “If I told him (a completed portrait of Pablo Picasso) (1934) by Gertrude Stein (1874-1946). Both were presented with the theater darkened and a simple card projected on the back wall of the name of the work and the composer.

The Heidsieck piece is a poignant and bittersweet scenario alleged to be at least partly autobiographical. The Stein was a poetic portrait of her friend, Pablo Picasso. It was in Stein’s own unique take on language and left one wondering why Stein’s work is not even better known than it is.

And for the finale the Other Minds Ensemble was joined by a frequent guest artist, the justly renowned pianist Sarah Cahill in a seldom performed work by American Composer (and Gertrude Stein collaborator) Virgil Thomson (1896-1989). “Capital Capitals” (1917-1927) utilizes a Stein text. Thomson and Stein enjoyed several successful collaborations (including two operas) with Thomson setting Stein’s words to music.

The text, designed with musical analogies in mind, was presented uncensored with a disclaimer in the program. The text, a bit dated, would not be considered politically correct by today’s standards. It is a celebration of the ancient capitals of Provence (Aix, Arles, Avignon, and Les Baux). The music was written ten years after the text and shows the same collaborative affinity demonstrated in the operas.

The ensemble appeared to have a great deal of fun with the punning language and the music such a good fit. The audience clearly agreed.

Scandalnavians

Day 4: One of the things that has characterized Other Minds concerts over the years is the attempt to include the world outside of the United States. This year the international artists mostly come from that same territory which Mr. Amirkhanian and Ms. Law traversed on their journey in the early 1970s. Jaap Blonk, who had already performed in from the Netherlands, Enzo Minarelli, from Italy. We would on this night also be introduced to Sten Hanson (1936-2013), Ottar Ormstad , Taras Mashtalir , Lily Greenham, Åke Hodell, Sten Sandell, and Tone Åse.

The evening opened with tape presentations of two pieces by Sten Hanson (1936-2013). Che (1968) and How Are You (1989). The first was a deconstruction of words of Che Guevara and the second a phonemic deconstruction and electronic manipulation of the three words of the title.

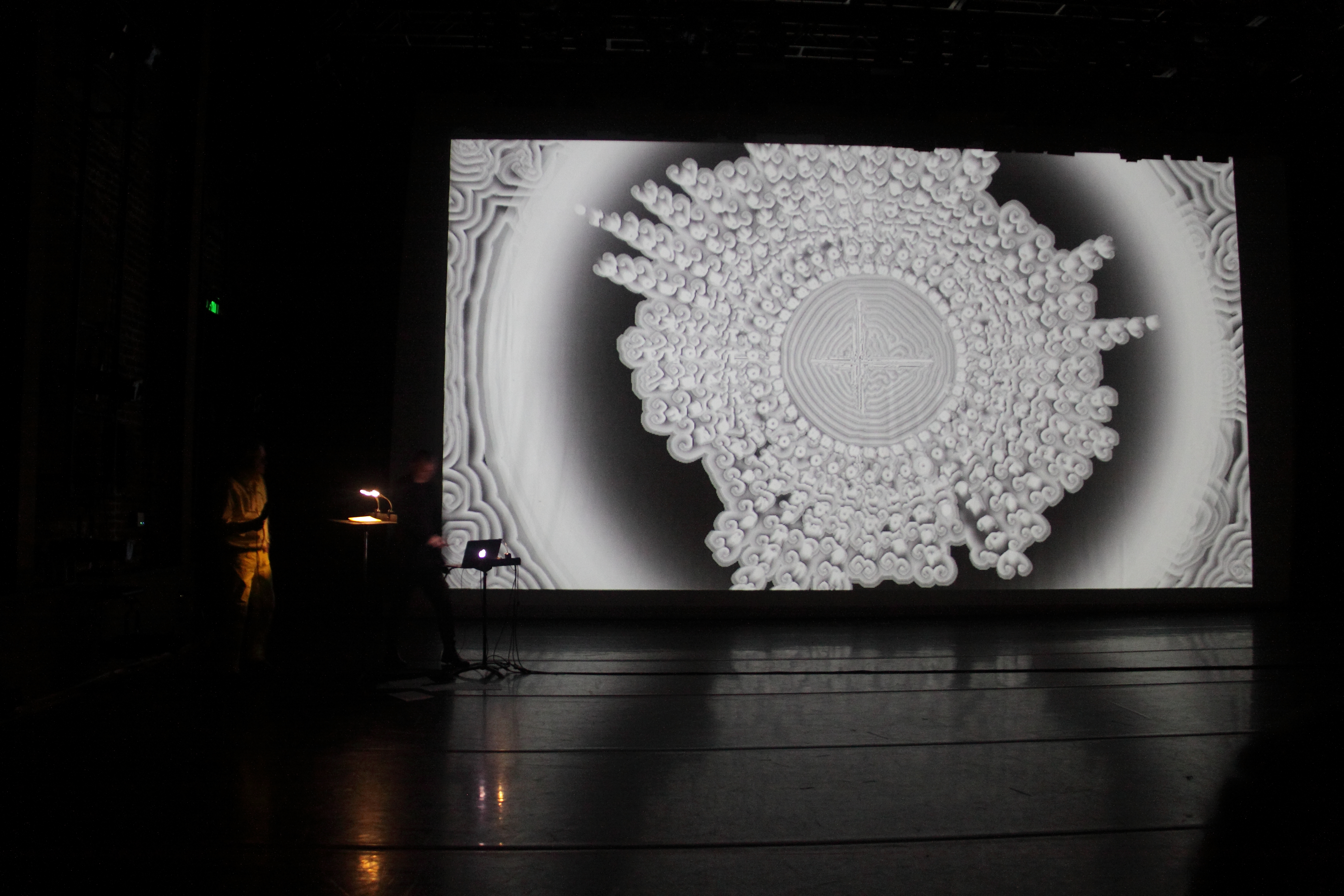

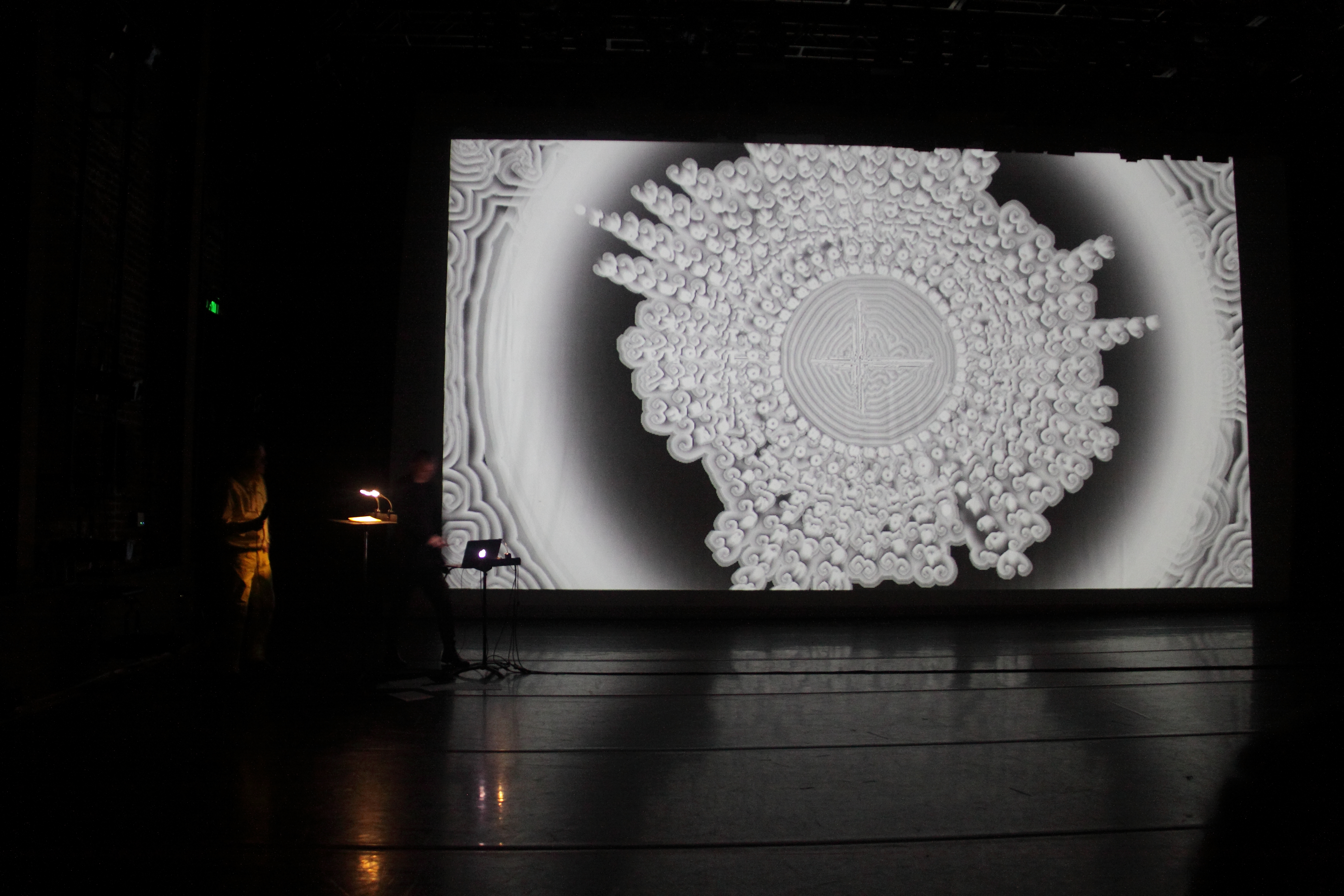

Then, in a significantly darkened hall, we were introduced to the work of Ottaras, a duo consisting of Russian composer Taras Mashtalir and Norwegian poet/artist Ottar Ormstad. Standing stage left of the projection screen which covered almost the entire back wall Mashtalir worked on his laptop (producing some heavy rumbling that shook the walls and was felt in the listener’s body). This writer’s first impression was that of some sort of IDM (Intelligent Dance Music) or ambient rave soundtrack. It accompanied some striking (mostly) black and white images which took center stage on the screen at the back wall. Slowly, at first imperceptibly, Ormstad wove some vocal sounds into the fabric. It was the U.S. premiere of a 2018 work entitled, “Concrete”. It was in four sections (or movements if you will) each separately titled, “Long Rong Song”, “Navn Nome Name”, “Kakaoase”, and “Sol”.

The strange swirling images, sometimes with words or parts of words moved across the back screen while the two performers, barely visible, worked with their instruments (computer and voice) to create a soundtrack for the images. Much like the non-syntactic use of sounds and language, the musical accompaniment was comprised of rather minimalistic utterances orchestrated in a wide range of frequencies with frequent heavy bass sound which provided a tactile component. All in all a rather mystical experience, exactly the cutting edge one looks for when attending an Other Minds production.

The performers seemed touched, perhaps even a bit surprised by the very warm response from the audience who seemed to connect rather easily to this unusual and very sensual experience.

The first half of this night’s concert concluded with the presentation of two more tape pieces, Lily Greenham’s “Outsider” (1973) and Åke Hodell’s “Mr. Smith Goes to Rhodesia” (1970). As in previous tape presentations a static photograph with titles was projected on the back wall in the darkened theater.

The Greenham piece is a solo monodrama in which the speaker (Greenham) is accompanied by an electronic chorus of her own voice. Hodell’s piece is clearly a protest piece about racial oppression by Ian Smith (Rhodesian Prime Minister 1964-1979) in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia). It is like the Greenham piece in that it utilizes a chorus but here the chorus is actual children gathered by the artist to speak/echo the lines of the narrative which contrasts the colonial narrative with both Hodell and the children periodically intoning, “Mr. Smith is a murderer.” The contrast was chilling and the pause for intermission a welcome respite.

The second half of the program began with a solo performance by Tone Åse, another world premiere. She performed her work, Ka? (2018) for voice and electronics. In this piece she works with the sounds of questions, hesitations, and the sound of dubiousness deconstructing words, phrases, sounds and manipulating them vocally and electronically in a piece whose low volume and sparse sounds certainly evoked the intended emotions.

After a brief acknowledgement of the appreciative applause the next performer, Sten Sandell sat down at the keyboard stage left and began the performance of Voices Inside the Language (2018), another world premiere. Again this experience had a similar sparse, almost minimalist approach. It was a collaboration that echoed the first night’s Coolidge and Curran performance and presented an entirely different sound world.

Almost before the audience realized the collaboration was over Åse discreetly left the stage leaving Sandell to perform his work, “vertikalakustik: med horisontell prosodi” (2017). Here was a near complete deconstruction of language using simply phonemes, individual sounds. With voice, piano, and projections on the back screen, Sandell delivered his necessarily minimalistic piece.

Both Sandell and Åse briefly acknowledged the applause bringing to an end this most satisfying international segment of the festival.

Good Luck with/for/on/in/at Friday the 13th

Described as an antidote for triskaidekaphobia (fear of the number 13), this evening’s program featured primarily California based artists including Amy X Neuberg, Mark Applebaum, Charles Amirkhanian, Carol Law, and (the one non-Californian) Enzo Minarelli.

The most famous victim of triskaidekaphobia was the Austrian/American composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951). Curiously for the sake of the present subject matter, Schoenberg invented sprechstimme (speech song), a sort of half sung/half spoken style of performance for many of his vocal scores. His unfinished opera, Moses und Aron (1932) uses it and ends the second (and last completed) act with Moses singing/speaking the following words: “O Wort, du Wort, das mir fehlt!” (in English: “O word, thou word, that I lack!”) Indeed the theme in the composer’s libretto is centered in part around Moses’ inability to articulate his ideas. (Aaron was the man of words, Moses the charismatic leader) Here, tonight, we were presented with artists who have grappled similarly (as all artists do) with the issue of expression and their unique solutions to the problem. (By the way the spelling, “Aron” is not a German spelling, it is Schoenberg’s truncation of the name so that the title would not have 13 letters.) The poor man probably wouldn’t have survived this night.

Projection of Applebaum performing with view of the composer/performer stage right as well.

The night opened to a darkened stage with the projection of one of those info/program note cards on the back wall. The presentation was of a tape piece by Stanford professor (and Other Minds alumnus) Mark Applebaum. Since the darkened stage and the all too brief bow taken by the composer exceeded the limits of this writer’s photographic skills I offer the above photo of Mr. Applebaum from previous Other Minds program.

The piece at hand on this Friday the 13th was, “Three Unlikely Corporate Sponsorships” (2016) which had it’s premiere at Stanford. The three sections were entitled, “Nestlé”, “General Motors”, and “Haliburton”. The mocking and humorous content was such that there was no doubt that the three named corporations were not involved in the creation and funding of this work. Like some of his predecessors this week Applebaum is prone to political commentary in his music whose sound appeared to take place in a stereo sound field with some antiphonal effects. Words were used, deconstructed, used again and never once were they used in a complementary fashion. This is, in its way, a protest piece.

As I said, Applebaum came out only briefly (with a smile on his face) to acknowledge the very amused and appreciative audience. One senses that protest against corporate greed is hardly an unpopular theme with this self selected audience which greeted this work with obvious satisfaction.

Amy X Neuberg is a well known performer in the Bay Area and is also an alumnus of Other Minds. Neuberg studied both linguistics and voice (at Oberlin College), and electronic music (at Mills College). She has a strong well-honed soprano voice and has developed her own unique mix of language and music in compositions that defy easy categorization.

Neuberg graced us with “My Go”, “Christmas Truce: a journal of landlord/tenant situations”, yet another world premiere for this series, “Say it like you mean”, “That’s a great question (A Jerry Hunt Song Drape)”, and, one of her classics, “Life Stepped In”.

Neuberg’s work is a striking and unique combination of linguistic wizardry, cabaret style song writing, probably some rock and pop sensibilities, and the indefinably unique way in which she integrates voice and electronics with a touch of drama at times. Her work is permeated with humor but also with social critique. As is always the case (at least in this writer’s experience) her performance was greeted with warmth and appreciation.

Following intermission we were again treated to the substantial performing skills of Enzo Minarelli who graced us with a generous selection of his own works including, “La grandeur di Ghengis Khan” (The grandeur of Ghengis Khan) comprised of eight vocal tracks and three noise tracks, “Il supere scopo di vita” (Knowledge as the purpose of life) “I nomi delle città come inno nazionale per Sinclair Lewis” (The names of the cities as national anthem to Sinclair Lewis) another multi-track work, and Excerpts from Fama: “Ciò chevoglio dire” (Fame: What I Want to Say): “Affermasi senza chiedere” (To succeed without asking), “Che teme il dolore (use la medicine della religion)” (Those who fear pain fuse the medicine of religion), “Alla ricerca del suono farmacopeo” (Seeking the pharmaceutical sound) and “Poema”.

In addition to their described meanings and verbal content these works were about the beauty of the Italian language and the beauty of the sound of the performer’s voice as well as the accompanying performance. Minarelli is apparently a performer of high energy. He performed on five of the six days and attended the last night as well seemingly all in a weeks work.

Once again the fairly minimalist lighting strategies were remarkably effective. Projections on the back wall along with Minarelli’s strong stage presence made for a striking performance of these works.

Minarelli was like a poet from a cabaret in some lost Fellini film fraught with intelligence, drama, passion, and humor.

Any of the above led the audience in some degree to the notion that what had just transpired would be a tough act to follow. Certainly this was true for Mr. Minarelli but, rather than a denouement or even a cooling down there was a shift of gears, a transition if you will, to yet another universe of creativity.

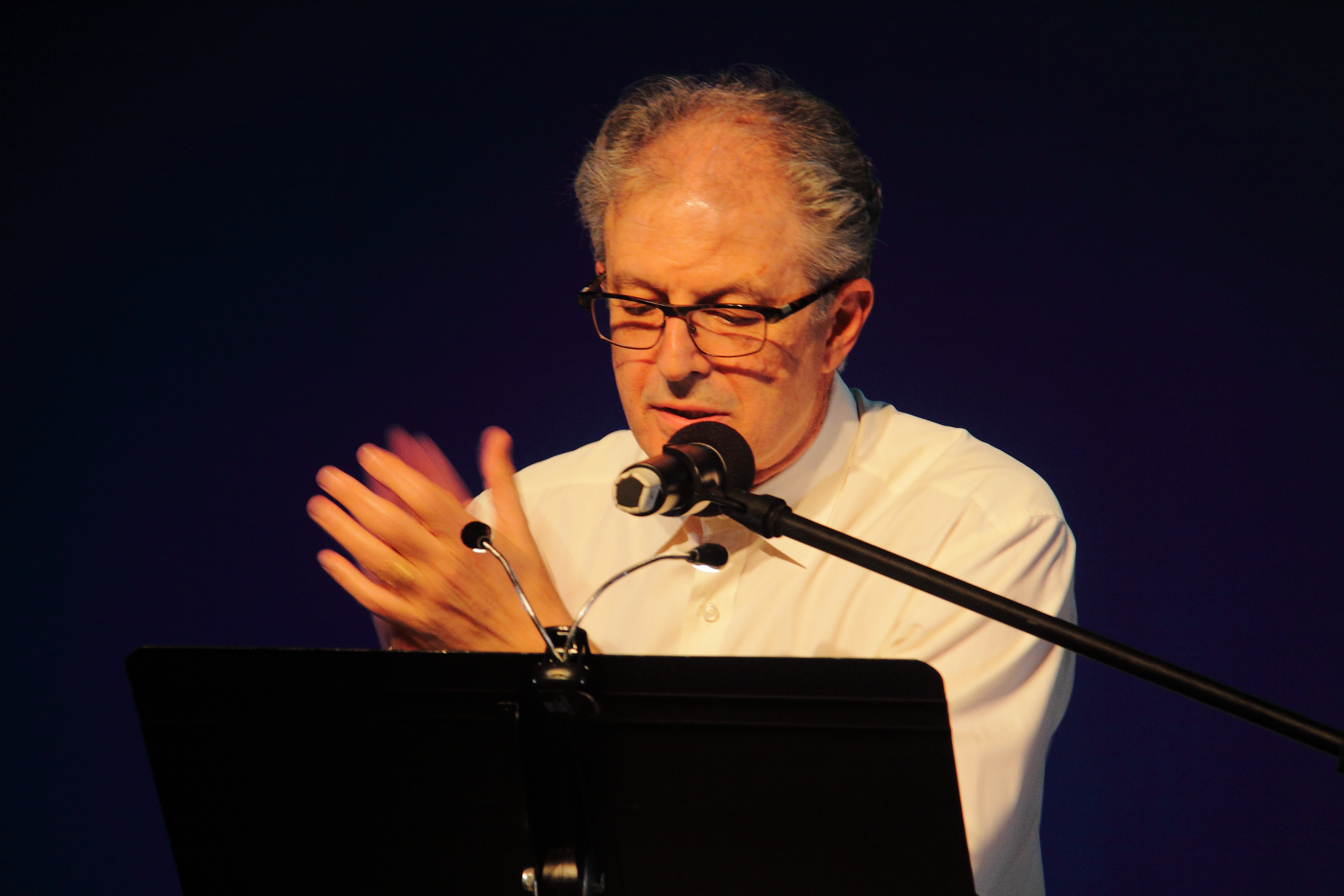

We were next presented with a fairly rare experience. We got to hear Other Minds’ executive and artistic director perform some of his own dalliances with languages and vocal utterances. Charles Amirkhanian, no longer wearing his jacket but rather a long white shirt, came on stage with this wife and partner, in both life and artistic crimes, Carol Law. Together they shared some of the inspirations of their (obviously still in progress) long strange trip.

In addition to being a photographer, Carol Law is a collage artist and has also been involved in the design of a few of pieces of Other Minds collectibles such as the t-shirts created for this year and several from previous years. What is a bit lesser known are her collaborative efforts with Charles Amirkhanian. The above image, for example, demonstrates the striking, slightly disturbing images that characterize the first work on tonight’s program, “History of Collage” (1981). Carol’s images were accompanied by a live recitation by Charles of a text which is actually about collage but is manipulated by a cut up technique. Here we saw images and heard the spoken text. For the next two collaborations Amirkhanian took his microphone and did his recitation in front of the projection screen creating effects not unlike the light shows and projections one might have seen in one of Bill Graham’s productions at the Fillmore Theater some 50 years ago. That is not to say that the intent or effect was nostalgic or historical, just that it seems to exist in a parallel universe. The long white shirt thus became a part of the projection screen with Amirkhanian moving dynamically along with the speaking of the disjointed texts.

The visual imagery was both striking and unique and held this writer, if not the entire audience, in thrall to a powerful sensual onslaught.

Hypothetical Moments (in the intellectual life of Southern California) (1981) is another of these cut up texts, this time an intercutting of Edith Wharton’s, “Glimpses of the Moon” and what Amirkhanian describes as “the gruff drugged-out reportage of a Yankee baseball game”, Ted Berrigan and Harris Schiff’s, “Yo-Yo’s with Money” (Amirkhanian is an avowed baseball fan). These were spoken over an improvisation done on an out of tune harpsichord modified by an Eventide Harmonizer.

The pair stepped on stage together to acknowledge the very appreciative applause. Indeed this was a rare and precious experience seeing them perform together and, though they did not eclipse the previous artists, they clearly established their parallel universe in the shared multiverse of sound poetry. These are wonderful performance pieces.

So…how do you follow that? Well, apparently with some solo Amirkhanian. As noted previously, Charles has been writing and performing his brand of vocal gymnastics since at least 1969. Two of his works, “Just” (1972), and “Heavy Aspirations” (1973) were included on that anthology mentioned at the beginning of this review.

Amirkhanian has taken the stage at least twice before at Other Minds performing his own text sound works. Tonight he presented, “Maroa” (1981), a sort of homage to a street in his home town of Fresno, “Ka Himeni Hehena” (The Raving Mad Hymn, 1997), a celebration/deconstruction of the Hawaiian language, “Marathon” (1997), a two voice poem which is like a nostalgic parody of the fundraising which Charles did so many times for KPFA, and, one of this best known works, the gently humorous “Dutiful Ducks” (1977) which involves rhythmic speaking and deconstruction of words on tape to which he reads live and (mostly) in sync. As with most of what we all heard on these days, live performance IS the point.

INK Conclusion

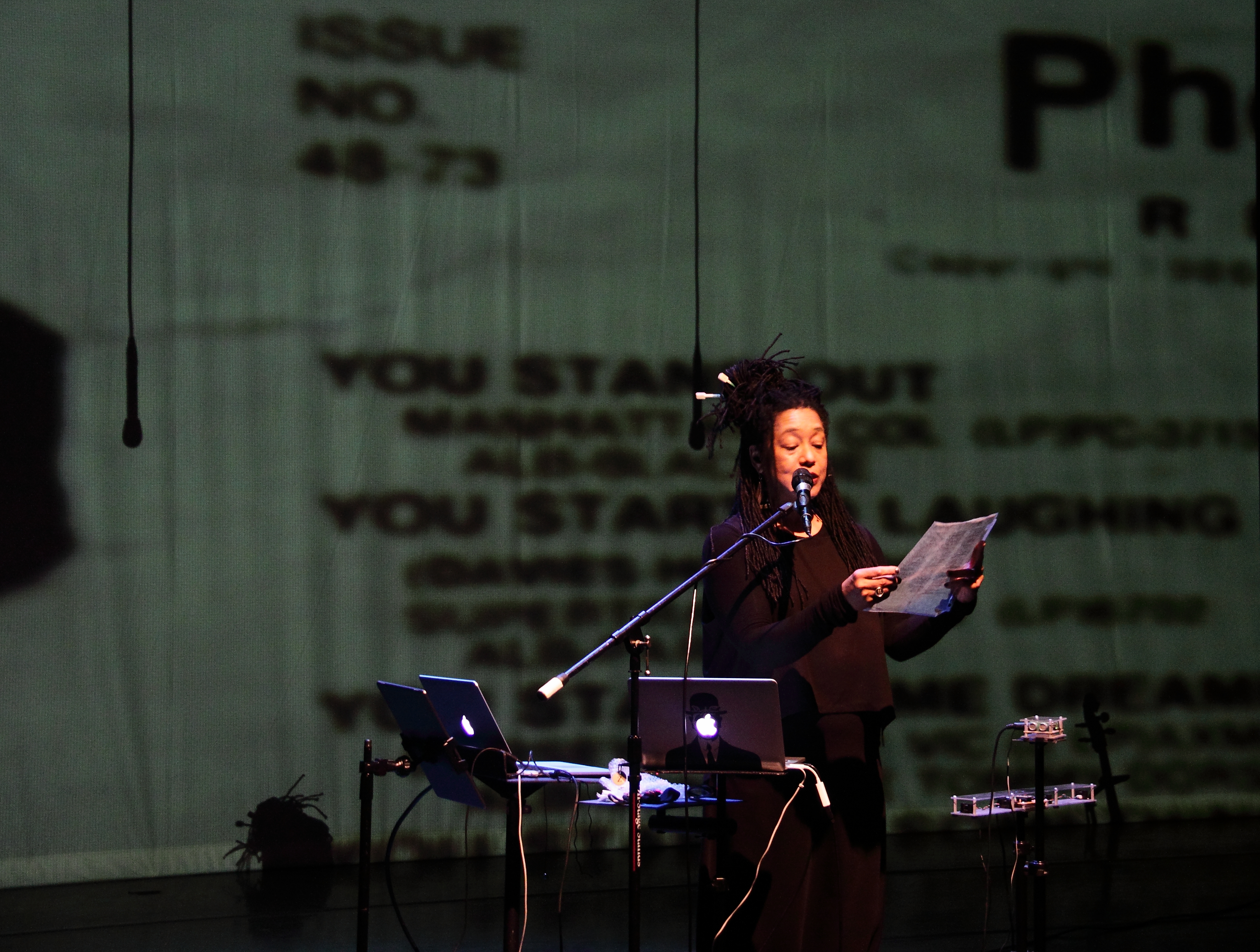

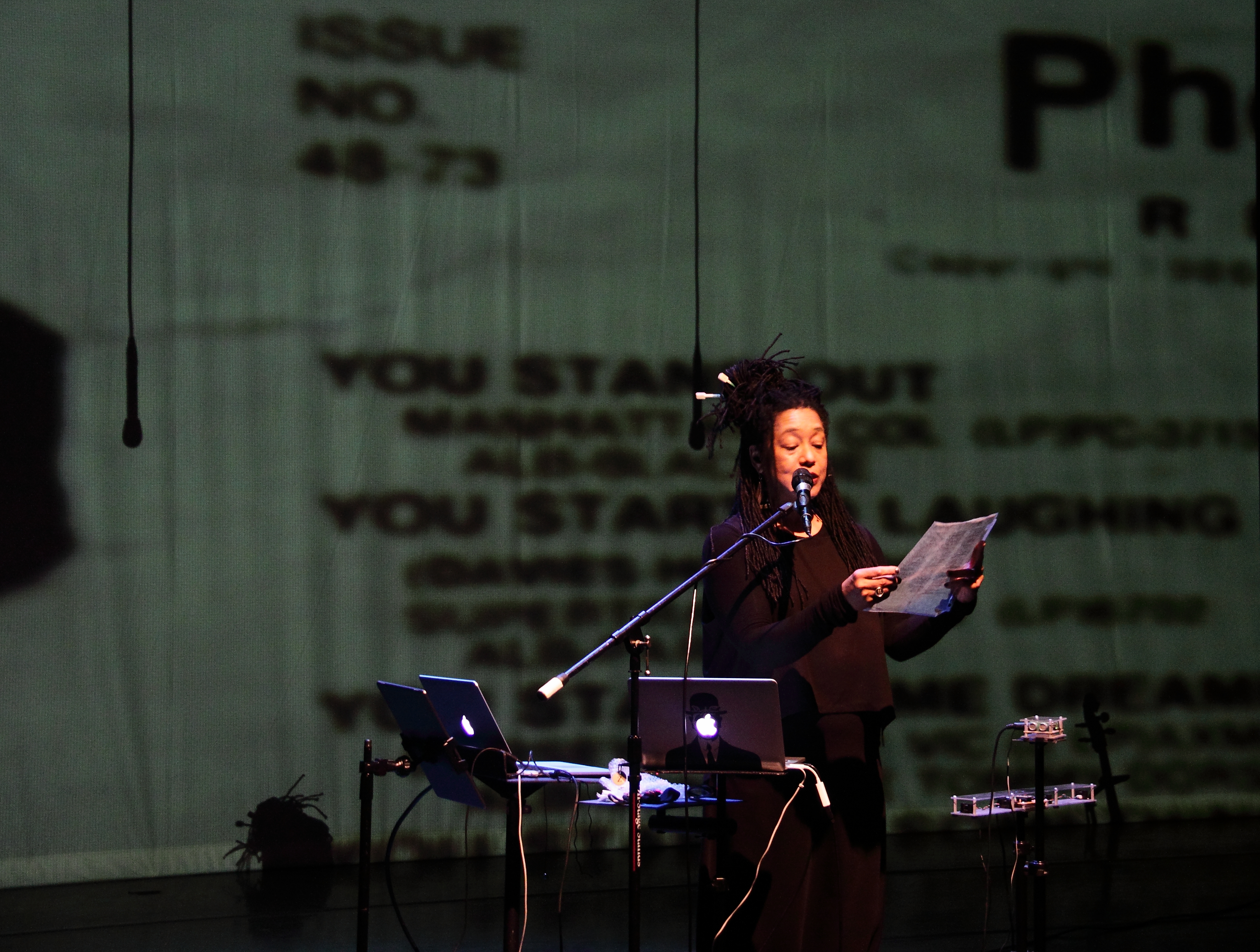

Day 6 featured beloved Bay Area diva (and Other Minds alumnus) Pamela Z. While one might note that, like Amy X Neuberg, she has a powerful, trained soprano voice and relies on electronics, her results are an entirely different animal. Some of Z’s specialized proximity controlled electronics are artistic creations themselves and play a part in the theatrical component of her performances.

Pamela Z’s performances were enhanced tonight with video and slides such as this projection which supported her performance of Typewriter/Declaratives.

Like Neuberg, Pamela Z does a sort of cabaret style performance. On this night she graced us with, “Quatre Couches/Flare Stains” (2015), “Typewriter/Declaratives” (2015), “33 Arches” (from a larger work called, Span, 2015), “Pop Titles: You” (1986) and the SF premiere of “Other Rooms” (2018).

Z’s skills at writing for chamber ensemble were displayed in 33 Arches, a section of a larger work called Span.

Most commonly seen as a soloist with electronics, it was a wonderful opportunity to hear a portion of one of her recent works which involved writing for more conventional instruments in addition to her voice and electronics. This was done also in conjunction with video.

Pamela concluded with a performance of one of her classic works, “Pop Titles ‘You'” (1986) enhanced by the back wall projection of the text source for the work, a page of the now defunct Phonolog report which was commonly found in record stores “back in the day” as they say. Z worked for a time at Tower Records.

Like Amy X Neuberg, Pamela Z was treated to a warm round of appreciation from this adoring home town Bay Area audience.

Next came another of the artists who appeared on the 10+2 anthology, Beth Anderson-Harold. She was accompanied by Other Minds intern and percussionist, Michael Jones. Beth Anderson, originally from Kentucky, exudes a sort of midwest wholesomeness that belies a complex and assertive artist. She is now based in New York but has strong roots in the Bay Area having worked with Charles Shere, John Cage, Terry Riley, Robert Ashley, and Larry Austin.

Her performances of “If I Were a Poet” (1975), I Can’t Stand It” (1976), “Crackers and Checkers” (1977), “Country Time” (1981), “Killdeer and Chicory” (2005), “Ocean, Motion, Mildew, Mind” (1979), and “Yes Sir Ree” (1978) were delivered with a powerful energy and enthusiasm. She seemed almost surprised at the warm reception her performance received. It was yet another example of the incredible variety that this genre of music embodies.

Anderson’s delivery was powerful, ecstatic, and assertive.

This sixth day of the varieties of sound poetry was brought to a conclusion first with three tape works by fellow KPFA (1990-2005) radio producer Susan Stone. The works presented were, “Couch” (from House with a View, 1989), “Ruby” (from House with a View, 1993), and “Loose Tongues” (1990). All are basically Stone’s personal take on radio theater which she describes as, “Cinema in the Head”. Stone took an all too brief bow to acknowledge the applause.

Though the audience’s attention seemed not yet to have flagged we were given an infusion of energy from the seemingly always energetic Jaap Blonk. He presented six of his works to conclude the evening, “Dr. Voxoid’s Next Move”, “Onderland” (Underland, excerpts), “Rhotic (Phonetic Study #1, about the R), “Muzikaret (Music Made of Rubber)”, “Cheek-a-Synth (Solo for Cheek Synthesizer)”, and “Hommage à A.A. (for Antonin Artaud).

Blonk’s seemingly boundless energy took him around the stage at times.

Blonk did a lovely thing to cap off this mind bending week (almost) of performances. He engaged the audience in a call and response improvisation. As these things generally go he began with fairly simple sounds and progressed to longer and more complex sound groupings which challenged the audiences attention and repetition skills, a task they/we performed with great joy and amusement.

Blonk leading the call and response performance with the audience which concluded the series.

Twenty performers, four of whom had appeared on that wonderful anthology, kept the ODC Theater packed to near capacity on all six nights. That alone is a feat. What cannot be satisfactorily communicated in a mere article is the energy and focus of both the performers and the enraptured audience whose attention never seemed to flag as they/we were lead down unfamiliar paths to little heard universes of ideas and sounds.

This expanded festival also included one of the most spectacular program books this writer has ever seen from Other Minds. Mark Abramson did the eye popping graphic design which featured no fewer than four different covers and very useful texts and photographs documenting the works performed and their history. The t-shirts were another of Carol Law’s successful designs. These may be highly collectible and, as of this writing, are still available through the Other Minds website.

In an promotional article entitled, “Other Minds 23: In the Beginning was the Word” I obviously used a biblical quotation (John 1: 1 for those interested). In fact the only religious thing going on here was the spiritual magic of astoundingly talented performers, and a mighty unusual gathering of Other Minds in terms of the enthusiastic audience. But I would be remiss if I did not take note of the fact that this fabulous marathon was done in six days. I’m guessing we all rested on the seventh.

Every year on June 21st, the Summer Solstice, there is a rather unique concert event in which musicians from the Bay Area and beyond gather in celebratory splendor in the sacred space of the Chapel of the Chimes in Oakland. The chapel is a columbarium (a resting place for cremated remains) and a mausoleum. The space is in part the work of famed California architect Julia Morgan.

Every year on June 21st, the Summer Solstice, there is a rather unique concert event in which musicians from the Bay Area and beyond gather in celebratory splendor in the sacred space of the Chapel of the Chimes in Oakland. The chapel is a columbarium (a resting place for cremated remains) and a mausoleum. The space is in part the work of famed California architect Julia Morgan.