Like many innovative young artists in New York City in the early 60s Meredith Monk had to train musicians to work with her unusual vocal methods. Her first album, Key (1971), was the first time her vocal art began to be dispersed outside the intimate, neo-bohemian loft space where the album was recorded. After graduating from Sarah Lawrence College in 1964 Monk moved to Manhattan where she and many other young, creative experimental musicians populated what became known as the “downtown scene” or SOHO. Many musicians worked with her over the years including composer/cellist Robert Een, Pianist Anthony De Mare both of whom incorporated their extended vocal techniques learned in the loft of the master herself.

Bang on a Can was formed from a very similar aesthetic (that of providing an alternative to the “uptown scene” which generally refers to the “establishment” or “mainstream” of classical music epitomized by Julliard and Lincoln Center. Founded in 1987, Bang on a Can and their subsequent touring group, Bang on a Can All Stars (begun in 1992) can be said to be another generation’s effort to achieve what Monk and the many musicians who followed such as Philip Glass, Steve Reich, LaMonte Young, among many others whose musical vision stood in contrast to the established uptown, more academic leanings.

It was Bang on a Can’s transcription of Brian Eno’s famous studio produced album (no live musicians), “Music for Airports” that demonstrated their ability to revision some of the work of their forebears and bring it into the concert hall. This is pretty much what we see here in this loving collaboration/tribute to one of New York’s finest composer/performers from the early downtown/SOHO era.

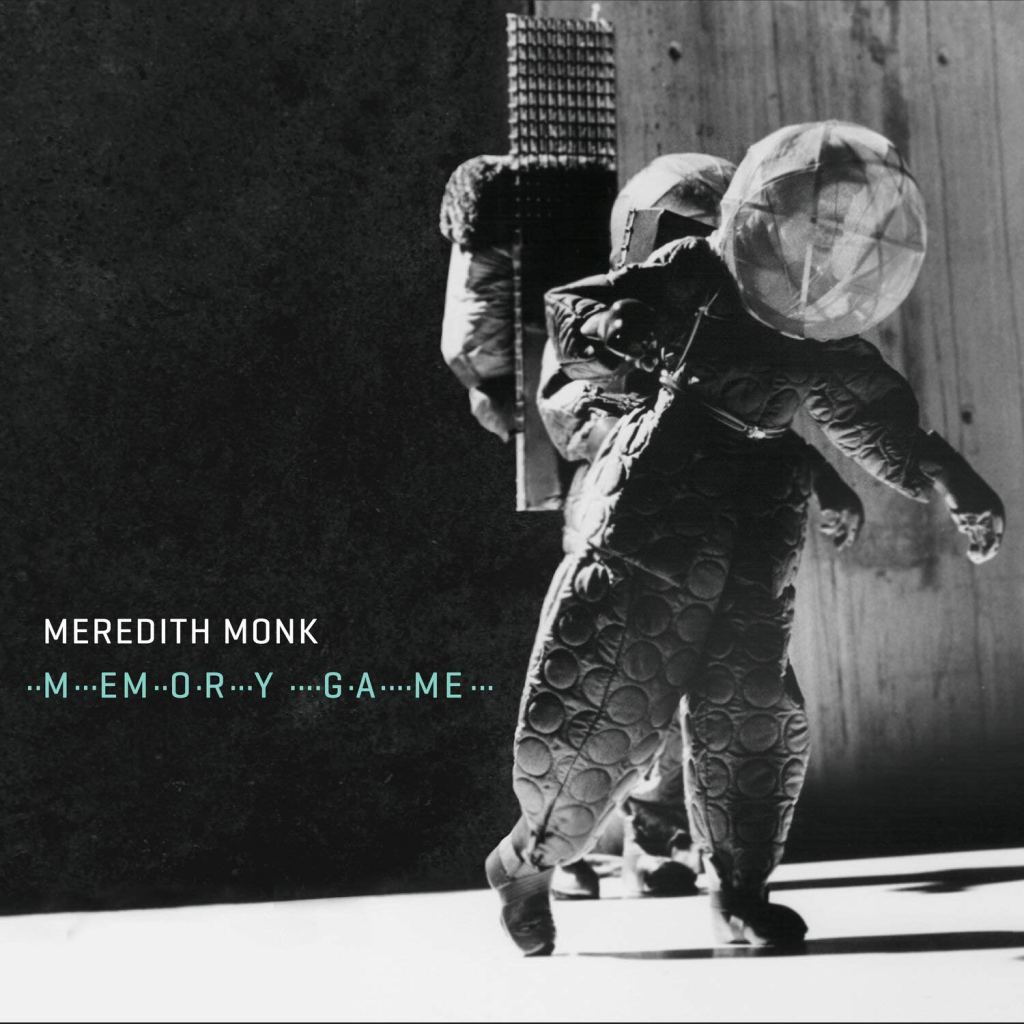

Monk began her artistic life as a dancer and dance/choreography remains an essential part of her artistic vision. 2014-2015 marks the 50th anniversary of Meredith Monk as a performer. “–M—EM–O-R—Y —-G-A—-ME—” (2020) is a wonderful production which sits somewhere between a “greatest hits” record and that of another generation’s reverent celebration of a unique artist. Bang on a Can shares the duties of transcription and performing with Monk and her ensemble. Most of Monk’s work involves (generally) one to five musicians (playing minimalist style music) onstage but here we see an expansion into a larger ensemble not unlike her collaborations which resulted in one of her largest works, the masterful “Atlas” (1993) produced by the Houston Opera. (Would that a new recording of Atlas may eventually come from such a collaboration).

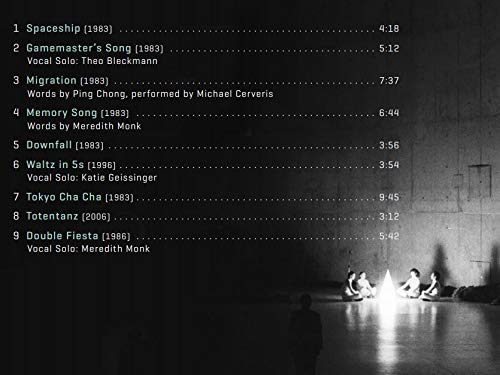

So what we have here is a combination of transcription, performance, but most importantly a respectful sharing out of a mutual educational experience between Monk’s ensemble and that of BOC. There are nine tracks comprising nine distinct compositions from Monk’s oeuvre. BOC composers provided transcriptions of “Spaceship” (Michael Gordon), “Memory Song” (Julia Wolfe), “Downfall” (Ken Thomson), “Totentanz” and “Double Fiesta” (David Lang). The other tracks appear in transcriptions by members of Monk’s ensemble: “Gamemaster’s Song” and “Migration” (Monk), “Waltz in 5s” (Monk and Sniffin), and “Tokyo Cha Cha” (Sniffin).

Monk’s ensemble in this recording consists of Meredith Monk, Theo Bleckmann, Katie Geissinger, Allison Sniffin, and guest artist Michael Cerveris. The Bang on a Can All Stars include Ashley Bathgate, cello and voice; Robert Black, electric and acoustic bass; Vicky Chow, piano, keyboard, and melodica; David Cossin, percussion; Mark Stewart, electric guitar, banjo, and voice; and Ken Thomson, clarinets and saxophones. The expansion of the ensemble adds favorably to the sound (as it did in Atlas) and the transcriptions enhance the music (as was the case in “Music for Airports”).

The 2012 collaboration produced by Monk’s House Foundation deserves mention here because it is a crowd sourced two CD production of covers by a variety of artists paying homage to Monk’s work. It is not clear if this release had any influence over the Memory Game album but it does speak to the influence of the artist.

ASIN : B00A1JCY1I

Fans of Meredith Monk and her various music/dance/theater works will find a comforting familiarity in these performances of music which, at one time were the leading edge of the new and experimental, now become familiar and, more importantly, embraced by another generation who clearly took the time to look, listen, and understand the work of this now acknowledged American Master. Those unfamiliar will find this a great introduction to Monk’s legacy.

Though chosen from a variety of compositions which date from 1983 to 2006, this selection comes together in a satisfying unity. The very tasteful album design is itself an homage to the look of Monk’s ECM recordings (under Manfred Eicher’s direction) who released the majority of her work. Kudos to the production team of David Cossin and Rob Friedman whose work here is among the finest of Bang on a Can Allstars’ recordings and a very satisfying addition to Monk’s discography. The little liner notes booklet includes an essay by the composer as well as a copy of the lyrics to “Migration” and “Memory Song”, just enough to inform and not overwhelm the casual listener. This is one fantastic release.