Though this was ostensibly Randall Goosby ’s show, the music making was a wonderfully integrated duo with pianist Zhu Wang, These two fine young musicians shared the virtuosic duties that the music in this concert demands. Both are clearly hard working and dedicated artists. Both have technical and interpretive prowess. And they clearly embody a mutual respect for each other.

The music on the program served to demonstrate the duo’s creative selection of music:

Coleridge-Taylor: Suite for Violin and Piano, op. 3

Brahms: Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Major, op. 100 (“Thun”)

Still: Suite for Violin and Piano

Price:Two Fantasies

Strauss: Violin Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 18

Curiously, due to this reviewer’s lack of familiarity with the violin and piano repertoire and having written some recent reviews of black composers’ music, the only familiar pieces were two of the three pieces by black composers. Now, overall, this is a marvelously chosen set of pieces that reflect the eclecticism and technical skill of both of these musicians.

The Brahms was perhaps the most familiar to audiences but the other works were equally substantive and worthy of being heard. It is these rather visionary choices that characterizes this duo as fresh and innovative. In addition their obvious knowledge of the music along with their enthusiasm and affection for it conspired to make for a delightful evening and even nudged this reviewer to try to become more familiar with the violin and piano repertory in general.

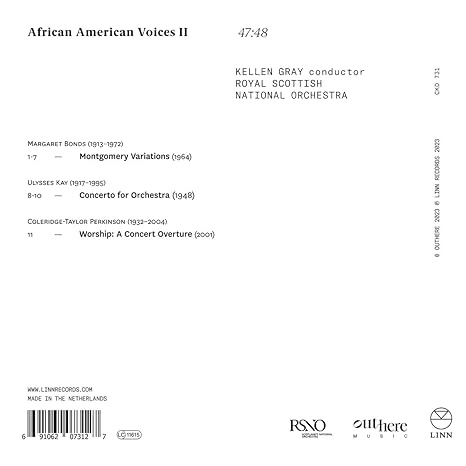

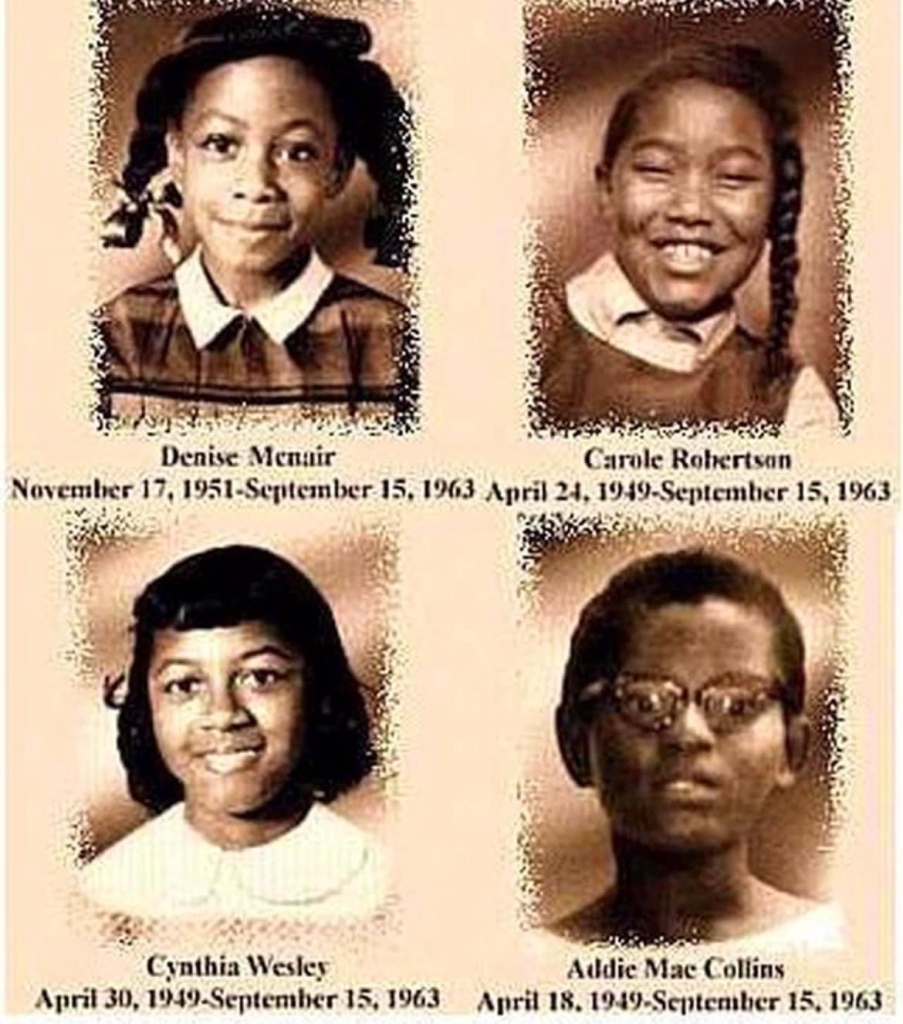

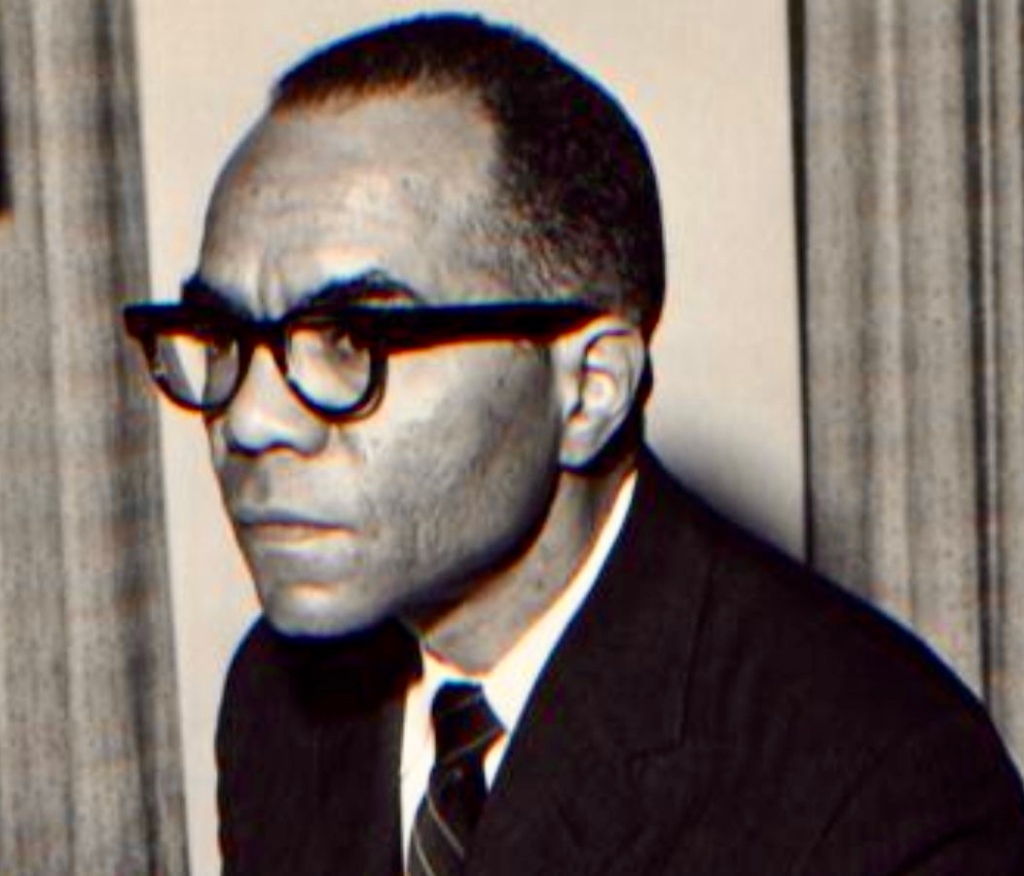

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) was a black British composer who has of late had a much needed revival of his music. He was named in honor of the celebrated British poet Samuel Taylor-Coleridge (1772-1834). During his rather brief lifetime, Samuel had been hailed as “the British Mahler but, after his death, his music lay largely fallow until revived by the late, great American black conductor, Paul Freeman (1935-2015). His revelatory series for Columbia records (now Sony) opened listeners’ ears to a fascinating selection of music by black composers internationally.

The Coleridge-Taylor opus 3 Suite for violin and piano (1893) is an early work cast in the high romantic late 19th century style of broad melodies and virtuosic demands. It served as the introduction to an intoxicating evening of (partly) seldom performed works alongside some fairly established works in the repertoire.

The Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) second violin sonata (of three) was written in 1879 and was named “Thun” after the Swiss city where he composed it. The three movements follow the classical fast, slow, fast structure common to this genre.

It is a product of high romanticism and it remains a staple of the repertoire. It, as with most of this composer’s music, is technically challenging for both instrumentalists. It was a fine vehicle to confirm the incredible technical skills of these young artists.

William Grant Still (1895-1978) was one of the finest composers of the early to mid twentieth century. Like Coleridge-Taylor and Florence Price (1887-1953), his music was lauded during his lifetime but was neglected until fairly recently in the aforementioned Black Composers set. These musical choices revealed another aspect of this delightful pair of musicians, that of being essentially musical archeologists uncovering forgotten gems much as Lord Carnarvan’s work availed the world to the marvelous Egyptian art of King Tut’s tomb.

Still’s Suite for Violin and Piano was inspired by three sculptures–Richmond Barthé’s African Dancer, Sargent Johnson’s Mother and Child, and Augusta Savage’s Gamin. Written in 1943, it synthesizes elements of blues, pop, and classical music to create musical description of this ethnically inflected visual art.

The three movements comprise essentially tone poems based on the visual artwork. It was after the second piece, depicting the Mother and Child sculpture that the spell cast by the duo’s that revealed the “Thrall” of this blog’s title.

Goosby embodies a calm and casual confidence and he let the audience know early on that it is OK to applaud after a single movement if you are so inclined. He has a warmth that put the audience at ease, embracing us in a most genial manner. There is, of course, nothing wrong with musicians who might seem more aloof but Goosby’s warmth was both generous and welcome. However, it became clear that this audience, after hearing that gorgeous second movement so beautifully played, paused in a seemingly hypnotic response to the impassioned performance that captured the beauty of the music. It felt as though we had become collectively and deeply engaged. That is the meaning of “thrall” and that was a beautiful experience that spoke of connections between composer, performers, and audience that represent the pinnacle of the art of chamber music performance. All three movements were wonderfully executed but that moment and the collective reaction was a truly moving experience.

Following a brief intermission we got to hear both of Florence Price’s two Fantasies for Violin and Piano (1933, 1940). Though I’ve become familiar with much of Price’s work (her three surviving symphonies and Goosby’s own reading of her two violin concerti have been released in the last couple of years) I had not heard these fantasies before.

Though written only seven years apart, the works embody distinctively different qualities. Both are certainly “capricious”, embodying a variety of moods, but the second is a bit longer and seemed to reflect the composer’s maturing style. Both works were enjoyable and seemed to please the audience.

This led us to the final work on the program, the Violin and Piano Sonata (1888) by Richard Strauss (1864-1949). Best known for his big orchestral tone poems and his grand operas, this was an early work which has found an audience due to its lyrical and friendly character.

It is cast in three movements, and it was at the end of the slow movement that we again saw/heard a sort of “agreed upon” silence in which the audience seemed to have shared a deep impact from that lovely movement played so passionately. No one applauded as a reverent silence came upon us.

The much busier third movement again presented the virtuosity and broad melodies of high romanticism. And there was applause and, much deserved standing ovations. It was a joy to have heard these talented and hard working musicians in an ecstatic night of chamber music.