The primary importance of this new release is, of course, the presentation of these two major works but it also an exposition of the diversity (or do you prefer, “heterogeneity”?) that can become obscured by well intended terms like, “Latino” and “Hispanic”, or even conductor Gustavo Dudamel’s “Pan American”. All are well intended but racial, nationalist, and other categories are insufficient on their own in recognizing the rich diversity inherent in their cultures. Here we go, just in time for Latin History Month.

The concise liner notes tell us that even the album’s title, “Fandango” has multiple meanings depending on cultural contexts. The fact is that no single style or genre can be said to be representative of the marvelous diversity that exists within their intended scope which attempts to represent practically the whole of the western hemisphere as is the case with this release. So, while Fandango is certainly about the musical works presented, it also touches on the issue of diversity by the choice of two major works separated chronologically by some 80 years and representing composers from Argentina on the one hand, and Mexico on the other. Two different cultures that share a language in both words and , to some extent, music.

The centerpiece of this album is, of courses, the concerto that Maestra Akiko-Meyers commissioned from Mexican composer Arturo Márquez Navarro (1950- ). I’m sad to say that I am only now learning of this composer but delighted in his mastery of the orchestra and the grand romantic gestures of a past era along with an acute and personal appreciation of the folk idioms of his culture. At first I was skeptical of a “mariachi” inspired concerto because such attempts, even the most sincere, don’t always seem to work. Well, that is certainly not the case here. This is a strong contender for regular inclusion in the current canon of widely performed violin concertos. This one is a masterpiece which poses challenges to the soloist (which give her a chance to show her virtuosity) and surround it with rich, subtly, ultimately beautiful orchestral textures that support the soloist but which demand much of the orchestra and its conductor as well.

The concerto (written in 2020) is in the traditional three movements. The first, entitled “Folia Tropical” (tropical leaves) embraces the spirit of late romantic concerti like those of Bruch and Brahms. It is an extended movement that introduces and develops many moods and themes. It is a big symphonic movement worthy of a symphony and it gives the soloist much to do and upon which to demonstrate her musical and interpretive skills all the while with a very busy orchestra accompanying her.

The second movement, “Plegaria” (prayer) is a hugely substantive chaconne, the baroque contrapuntal variation form with a repeating bass line and thematic variations over the harmonic structures supported by those notes.. At least that is my listener’s understanding. But what is not necessary to “understand” technically is the emotional impact of this movement. This is an amazing use of the form. The soloist moves into different roles, sometimes very much upstage, sometimes an adjunct to the orchestra, sometimes not there at all. There is a slow, meditative beauty in this movement which is also characteristic of the romantic idiom in which this is written.

The third movement, “Fandanguito” (little Fandango) is a somewhat lighter and very energetic finale one might expect in a movement following the previous deeply emotional ones. And the composer does not disappoint. He writes a joyous, energetic finale which nonetheless stands up as substantially as its predecessors.

The joy, to this listener, is to hear a master composer in collaboration with a fine soloist both technically and interpretively. The composer has integrated his experiences and study of his own cultural folk musics and infuses the spirit of the music into his grand romantic idiom. That is, the concerto does not, for the most part use direct quotation from folk sources but uses structural elements in his composition. Maestra Akiko Meyers discharges her soloist duties with both startling facility and a deep understanding of the music and the composer’s intent.

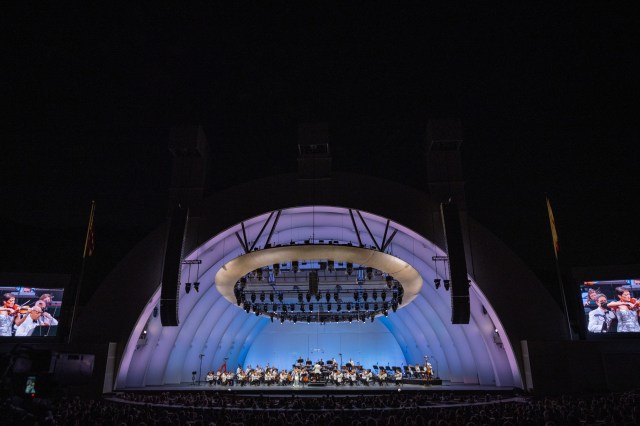

Gustavo Dudamel is a joyfully rising star who brings his cultural proclivities and his own lens on western orchestral music. He is an exciting and incisive conductor. I don’t know the extent of Dudamel’s study of Latin folk musics but he really gets this work and brings out the composer’s subtleties in this gorgeous and exciting concerto.

The “B side” as they used to be called is no mere filler, it is the entirety of the Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983) ballet, “Estancia” Op. 8 (1941). Here, 15 separate movements are used in a five scene scenario. The work, usually heard in its four movement suite format and, even more frequently, just the spectacular finale, the Malambo.

In addition to its large orchestra, the ballet calls for a singer/speaker soloist who acts as both narrator and as soloist with orchestra. In this performance the challenge is admirably met by baritone GUSTAVO CASTILLO, another shining light cultivated by El Sistema. He performs well in both his baritone vocal duties and his narrator task in which he speaks Spanish in an elegant and, I’d say, almost Shakespearean grasp of the beauty of the language. The man understands drama as well as music.

This ballet is clearly a masterpiece. It reminds this listener of Prokofiev if he was born in Argentina. Nothing derivative here though. This is an intensely entertaining work, as substantial as Romeo and Juliet, similarly constructed in relatively brief musical segments designed to accompany a dance whose scenario is the story of the “gaucho” or cowboy that lived and worked hard lives, lives that were romanticized into a poem by Argentinian poet José Hernández (1834-1886). (click on the word “poem” for a link to an English translation of the poem).

All that to say that this is a truly enjoyable and important release. A valuable addition to the discography of Latin classical music.