The stage at Kanbar Hall stands ready to receive performers on opening night of OM 18

OM 18 has been my fifth experience at the Other Minds festival. The most amazing thing about Other Minds is their ability to find new music by casting a wide net in the search for new, unusual and always interesting music. As I said in my preview blog for these concerts this year’s selection of composers was largely unfamiliar to me. Now I am no expert but my own listening interests casts a pretty wide net. Well this year I had the pleasure of being introduced to many of these composers and performers with no introduction save for the little research I did just before writing the preview blog (part of my motivation for doing the preview blog was to learn something about what I was soon to hear).

Danish folk trio Gáman

The first night of the series consisted of what is generally classified as “folk” or “traditional” music. Not surprisingly these terms fail to describe what the audience heard on Thursday night.

First up was the Danish folk trio ‘Gáman’ consisting of violin, accordion and recorder. This is not a typical folk trio but rather one which uses the creative forces of three virtuosic musicians arranging traditional musics for this unusual ensemble. On recorder was Bolette Roed who played various sizes of recorders from sopranino to bass recorder. Andreas Borregaard played accordion. And Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen was on violin.

The first piece, ‘Brestiskvædi’ was their rendering of this traditional song from the Faroe Islands (a group of islands which is under the general administration of Denmark but which has its own identity and a significant degree of independence). It struck my ears as similar in sound to the music of Scotland and Ireland, lilting beautiful melodies with a curiously nostalgic quality.

Next was a piece by Faroese composer Sunleif Rasmussen. It was the U.S. premiere of his ‘Accvire’ from 2008, a name derived from the two first letters of the instruments for which it was written (as we learned in the always interesting pre-concert panel). It was commissioned by this ensemble. The work reflected the composer’s facility with instrumentation and retained some suggestion of folk roots as well. It employed a rich harmonic language within a tonal framework in what sounded almost like a post-minimalist piece. The trio met the challenges of the music and delivered a lucid reading of this music which seemed to satisfy both the musicians and the audience.

The trio followed this with three more folk arrangements, two more from the Faroe Islands and one from Denmark. Like the first piece they played these had a similar ambience of calm nostalgia.

The Danish folk piece set the stage for the next work, a world premiere by one of Denmark’s best known living composers, Pelle Gudmunsen-Holmgreen. The piece ‘Together or Not’ from 2013 is an Other Minds commission. The composer, who was not present, wrote to Other Minds director Charles Amirkhanian saying, “the title is the program note”. While the statement was rather cryptic the music was not. This was less overtly tonal than the Rasmussen work and was filled with extended instrumental techniques and good humor. Again the instrumentalists demonstrated a comfortable facility with the technical challenges of the music and delivered a fine reading of this entertaining piece.

The nicely framed program continued with two traditional drum songs from Greenland (the violinist, holding his instrument rather like a guitar produced a sort of modified pizzicato technique which played the drum part). These haunting melodies seemed to evoke the desolate landscape of their origin.

The program ended with a Swedish polka and, in response to a very appreciative audience, an encore of another spirited polka. These were upbeat dance music that all but got the audience up and dancing. The audience seemed uplifted by their positive energy.

G.S. Sachdev (left) and Swapan Chaudhuri.

The second half of the first night’s concert consisted of two traditional Hindustani Ragas. These pieces are structured in aspects of the the music but allow for a great deal of repetition and improvisation in which the musicians bring the music to life. Hindustani music is deeply rooted in culture and spirituality. The ragas are associated with yogic chakras, moods and time of day. Their performance is intended to enhance the audience esthetically and spiritually.

G.S. Sachdev is a bansuri player. The bansuri is a wooden flute common in this type of music (though Sachdev’s level of mastery is hardly common). He was accompanied by the familiar tanpura drone produced by digital drone boxes instead of the actual instruments which produce the familiar drone sound that underlies Hindustani music performances. Swapan Chaudhuri played tabla. It is difficult to see the tabla as an “accompanying” instrument as much as it is a complementary instruments especially when played by a master such as he. Chaudhuri is the head of the percussion department at the Ali Akbar Khan school in San Rafael in the north bay. Sachdev has also taught there. Both men have ties to the bay area.

The musicians performed Raga Shyam Kalyaan followed by Raga Bahar. Originally I had thought of trying to describe these ragas in their technical aspects but my knowledge of Hindustani music cannot do justice to such an analysis. Rather I will focus on the performances.

Raga Shyam Kalyaan was first and received an extended reading. How long? Well I’m not sure but this music does create a sort of suspended sense of timelessness when performed well. Indeed that was the effect on this listener. The whole performance of both ragas could not have exceeded one hour but the performances by these master musicians achieved the height of their art in producing riveting performances of this beautiful music. Sachdev’s mastery certainly has virtuosity but his genius lies in being able to infuse his performance with spirituality from within himself and to impart that spiritual resonance to his audience. He was ably aided in that endeavor by Chaudhuri who, clearly a master of his instrument and connected with Sachdev, channeled his connection with the infinite.

The audience responded with great warmth and appreciation concluding the first day of the festival.

Composer, performer, designer, shaman Dohee Lee performing her work, ‘ARA’.

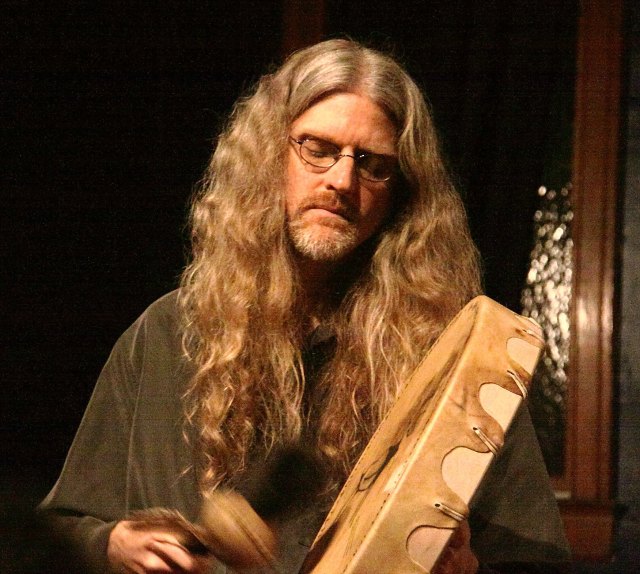

Friday night began with the world premiere of the music theater performance piece, ‘ARA’ by Korean-American artist Dohee Lee. Continuing with the spiritual tone set by yesterday’s Raga performances Lee introduced her multi-disciplinary art derived from her study of Korean music, dance and shamanism as well as costume design and music performance.

She was aided in her efforts by the unique instrument designed for her by sculptor and multi-disciplinary artist Colin Ernst. The Eye Harp (seen in the above photo) is an instrument that is played by bowing and plucking strings and is connected to electronics as well.

The art of lighting designer David Robertson, whose work subtly enhanced all the performances, was clearly in evidence here. This was a feast for the eyes, ears and souls. Dohee Lee’s creative costume design was integrated with the visually striking Eye Harp instrument. And the music with sound design processing her instrument nicely complimented her vocalizations. All were lit so as to enhance the visual design and create a unified whole of this performance.

Dohee Lee on the carefully lit stage off Kanbar Hall.

Her performance began slowly with Lee in her beautiful costume took on the role of a modern shaman conjuring glossolalia in shamanic trance along with choreographed movement and accompanied by her Eye Harp and electronic sounds through the theater’s great sound system. Like the raga performances of the previous night I wasn’t aware of how long this timeless performance lasted (the program said it was 10 minutes) . But I wished it would have gone on longer. Even with photographs the experience here is difficult to articulate. The sound enveloped the audience who viewed the carefully lit stage in the otherwise darkened hall as the sounds communicated a connection with the sacred.

I am still trying to digest what I saw and heard on this Friday night. I don’t know how most of the audience experienced this piece but they seemed to have connected with it and responded with grateful applause. She seemed to connect as both artist and shaman.

Anna Petrini performing with her Paetzold contrabass recorder.

Following Dohee Lee were three pieces for an instrument called the Paetzold contrabass recorder (two before intermission and one after). Paetzold is the manufacturer who specializes in the manufacture of recorders, forerunner of the modern flute. The square contrabass recorder is a modern design of this woodwind instrument. However, knowing the sound of the recorder in music of Bach and his contemporaries, gives the listener no useful clues as to what to expect from the unusual looking instrument pictured above.

Anna Petrini is a Swedish recorder virtuoso who specializes in baroque and modern music written for the recorder. At this performance she played her contrabass instrument augmented variously by modifications, additions of microphones, little speakers and electronic processing. These pieces were perhaps the most avant-garde and the most abstract music in this festival.

Anna Petrini performing on the stage of Kanbar Hall at the Other Minds festival.

The creative stage lighting provided a useful visual counterpoint to the music. The first piece, ‘Split Rudder’ (2011) by fellow Swede Malin Bang was here given it’s U.S. premiere. This piece is concerned with the sounds made inside the instrument captured by small microphones inserted into the instrument. The resulting sounds were unlike any recorder sound that this listener has heard. The piece created percussive sounds and wind sounds.

The next piece, ‘Seascape’ (1994) by the late Italian composer Fausto Rominelli (1963-2004) used amplification but no electronic processing. These abstract works were received well by the audience.

‘SinewOod’ (2008) by Mattias Petersson involved introducing sound into the body of the instrument as well as miking it internally and setting up electronic processing with which the performer interacts. Like the two pieces that preceded it this was a complex exercise in the interaction between music and technology which is to my ears more opaque and requires repeated listenings to fully appreciate.

Craig Taborn performing on the stage of Kanbar Hall at the 2013

The second concert was brought to its conclusion by the young jazz pianist and ECM recording artist Craig Taborn. Detroit born, Taborn came under the influence of Roscoe Mitchell (of AACM fame) and began developing his unique style. Here the term jazz does little to describe what the audience was about to hear.

Taborn sat at the keyboard with a look of intense concentration and began slowly playing rather sparse and disconnected sounding notes. Gradually his playing became more complex. I listened searching for a context to help me understand what he was doing. Am I hearing influences of Cecil Taylor? Thelonius Monk? Keith Jarrett maybe?

Well comparisons have their limits. As Taborn played on his music became more complex and incredibly virtuosic. He demonstrated a highly acute sense of dynamics and used this to add to his style of playing. I was unprepared for the density and power of this music. Despite the complexity it never became muddy. All the lines were distinct and clear. And despite his powerful and sustained hammering at that keyboard the piano sustained no damage. But the audience clearly picked up on the raw energy of the performance.

This is very difficult music to describe except to say that it had power and presence and the performer is a creative virtuoso whose work I intend to follow.

Amy X Neuberg along with the William Winant percussion group playing Aaron Gervais.

The final concert on Saturday began with the world premiere of another Other Minds commissioned work, ‘Work Around the World’ (2012) for live voice with looping electronics and percussion ensemble. This, we learned in the pre-concert panel is another iteration in a series of language based works, this one featuring the word ‘work’ in 12 different languages.

Amy X Neuberg singing at the premiere of Aaron Gervais’ ‘Work Around the World’.

Language is an essential part of the work of local vocal/techno diva Amy X Neuberg’s compositions and performance work. With her live looping electronics she was one instrument, if you will, in the orchestra of this rhythmically complex work. William Winant presided over the complexity leading all successfully in the performance which the musicians appeared to enjoy. The audience was also apparently pleased with the great musicianship and the novelty of the work. Its complexities would no doubt reveal more on repeated listenings but the piece definitely spoke to the audience which seemed to have absorbed some of the incredible energy of the performance.

Michala Petri performing Sunleif Rasmussen’s ‘Vogelstimmung’.

Back to the recorder again but this time to the more familiar instrument if not to more familiar repertoire. Recorder virtuoso Michala Petri whose work was first made known to the record buying public some years ago is familiar to most (this writer as well) for her fine performances of the baroque repertoire.

Tonight she shared her passion for contemporary music. First she played Sunleif Rasmussen’s ‘Vogelstimmung’ (2011) which he wrote for her. It was the U.S. premiere of this solo recorder piece. Vogelstimmung is inspired by pictures of birds and is a technically challenging piece that Petri performed with confidence. At 17 minutes it was virtually a solo concerto.

And then back to electronics, this time with Paula Matthusen who now teaches at Wesleyan holding the position once held by the now emeritus professor Alvin Lucier. Her piece for recorder and electronics, ‘sparrows in supermarkets’ (2011) was performed by Ms. Petri with Ms. Matthusen on live electronic processing. This was a multi-channel work with speakers surrounding the audience immersing all in a complex but not unfriendly soundfield.

Michael Straus (left) with Charles Amirkhanian

Some technical difficulties plagued the beginning of the first piece after intermission so the always resourceful emcee, Other Minds executive director Charles Amirkhanian took the opportunity to introduce the new Operations Director Michael Straus. Straus replaces Adam Fong who has gone on to head a new music center elsewhere in San Francisco.

Mr. Amirkhanian also spoke of big plans in the works for the 20th Other Minds concert scheduled for 2015 which will reportedly bring back some of the previous composers in celebration of 20 years of this cutting edge festival. No doubt Mr. Straus has his work cut out for him in the coming months.

Ström, part of the video projection

With the difficulties sufficiently resolved it was time to see and hear Mattias Petersson’s ‘Ström’ (2011) for live electronics and interactive video in its U.S. premiere. Petersson collaborated with video artist Frederik Olofsson to produce this work in which the video responds to the 5 channels of electronics which are manipulated live by the composer and the five lines on the video respond to the sounds made. The hall was darkened so that just about all the audience could see was the large projected video screen whilst surrounded by the electronic sounds.

The work started at first with silence, then a few scratching sounds, clicks and pops. By the end the sound was loud and driving and all-encompassing. It ended rather abruptly. The audience which was no doubt skeptical at the beginning warmed to the piece and gave an appreciative round of applause.

Paula Matthusen performing her work, ‘…and believing in…’

Next up, again in a darkened hall was a piece for solo performer and electronics. Composer Paula Matthusen came out on stage and assumed the posture in the above photograph all the while holding a stethoscope to her heart. The details of this work were not given in the program but this appears to be related to the work of Alvin Lucier and his biofeedback work on the 1970s. Again the sounds surrounded the audience as the lonely crouching figure remained apparently motionless on stage providing a curious visual to accompany the again complex but not unfriendly sounds. Again the audience was appreciative of this rather meditative piece.

Pamela Z (left) improvising with Paula Matthusen

Following that Ms. Mathussen joined another bay area singer and electronics diva, Pamela Z for a joint improvisation. Ms. Z, using her proximity triggered devices and a computer looped her voice creating familiar sounds for those who know her work while the diminutive academic sat at her desk stage right manipulating her electronics. It was an interesting collaboration which the musicians seemed to enjoy and which the audience also clearly appreciated.

Pamela Z performing Meredith Monk’s ‘Scared Song’

For the finale Pamela Z performed her 2009 arrangement of Meredith Monk’s ‘Scared Song’ 1986) which appeared on a crowd sourced CD curated by another Other Minds alum, DJ Spooky. Z effectively imitated Monks complex vocalizations and multi-tracked her voice as accompaniment providing a fitting tribute to yet another vocal diva and Other Minds alumnus. The audience showed their appreciation with long and sustained applause.

All the composers of Other Minds 18

37.765206

-122.241636