The first volume of this Bridge Records landmark series focused on Harry Partch’s (1901-1974) most likely best known works, a fine way to introduce this man’s unusual and brilliantly experimental music.

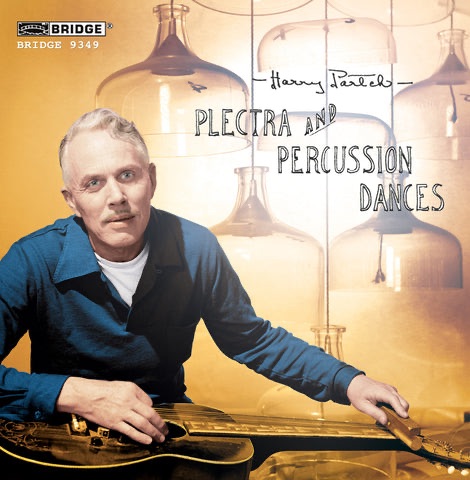

From this first volume, it is clear that great care was taken to produce the most authentic and complete versions of this music in dedicated, authentic performances on faithfully constructed copies of Partch’s unusual (and visually beautiful) instruments. The instruments themselves deserve a history and analysis but that is beyond the scope of this review. This is a great disc to introduce listeners to this man’s work.

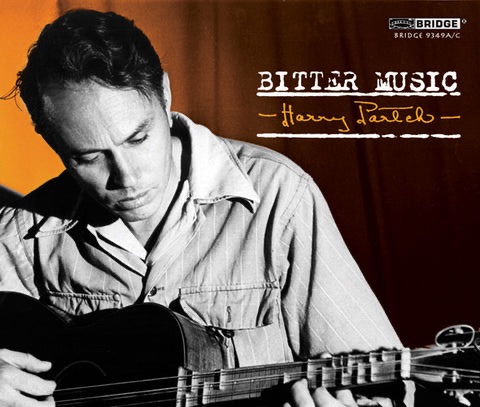

This second volume won a Grammy for the best classical compilation. It is largely a spoken word album, the title taken from Partch’s journal documenting his itinerant adventures and musical experiments. This is essentially an audio “Complete Works” edition in which the scholarship of text and performance are refined to represent as accurate a representation of this unique composer’s work as possible. Not as easy listening as the first volume but truly a gift to fans and performers.

The third volume, reviewed here, includes a heretofore unknown work by Partch gleaned from that careful reading of the “Bitter Music” diaries (along with other gems). This was actually my introduction to this recording project as Mr. Schneider graciously sent me a copy for review. This rekindled my romance with Partch’s music begun in about 1970 when I heard a 7” promotional disc which was bundled with my copy of Wendy Carlos’ Switched on Bach. That disc contained an excerpt from Partch’s Castor and Pollux among other composers.

Volume Four

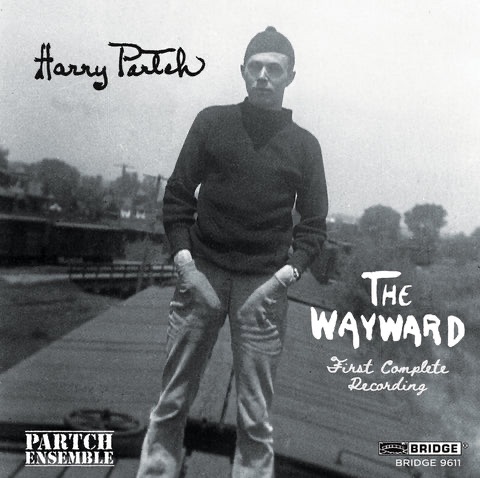

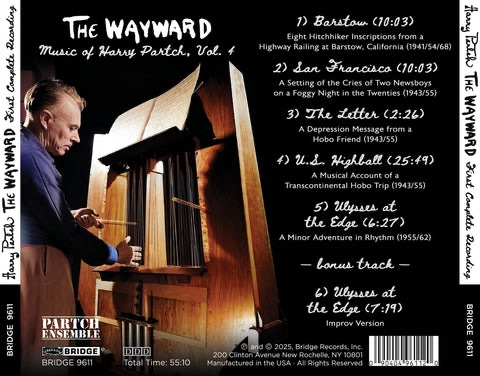

Now comes Volume 4 and it is loaded with Partchian glory in that it presents the first complete recording of these interrelated works, a sort of cycle of song cycles which, together make up a larger work, a “Meta-song cycle” titled, “The Wayward”. It is arguably his first large scale dramatic work, presented here in aggregate as once planned but never realized until now.

Each volume in this series truly does homage to Harry Partch and assures that his music will continue to have listeners well into this 21st century. There is no question in this listener’s mind, that this complete works cycle will stand for a long time as THE definitive and most complete version of Partch’s oeuvre for many years.

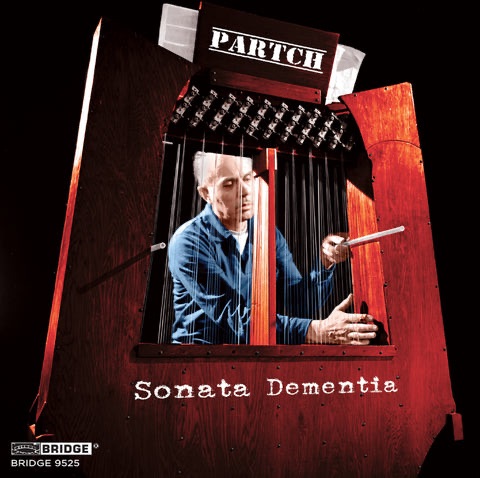

Even as a long time fan of Partch’s work such as myself continues to find delight in the care and attention to detail found in all of these releases. Enthusiasts will still enjoy the various prior media incarnations by the composer himself from releases on his own Gate 5 label and others which are still available as are subsequent recordings by Dean Drummond and others. But the present series features newly fashioned copies of Partch’s original instrument designs. Those instruments and their visually beautiful and imposing designs themselves become characters along with the musicians in staged live performances. This represents a major step in his artistic development which led to larger scale music theater and film scores later in his career.

It is hard to imagine this being done better and this series effectively situates Partch not simply as the obscure outsider experimentalist, but as a unique artist whose work informs and inspires the next generation of composers and performers. It also clarifies his music theater aspirations and sets the tone for the (hopefully upcoming) larger dramatic works in this ongoing series such as The Revelation in Courthouse Park (1960), The Bewiched (1955), and Delusion of the Fury (1968).

Indeed, Partch had an eye and an ear for the theatrical. His palette was the drama of the dispossessed, the hobo, riding the rails in a sort of proto-beat ethic that later gave rise to Jack Kerouac et al, whose Everyman tales in his novels shaped the subsequent artistic generation. Partch, with his exotic tuning theories broke free from the straight jacket of western music’s conventional tunings (and western concepts of drama) to tunings reconceived from their Pythagorean ideals of ancient practice to a modern alternative with the goal of finding new ways of expression. Kerouac experimented with writing and Partch with tuning. But both men struggled in at least partly voluntary exile from the mainstream of the society within which they found themselves. Partch’s dramatic backdrop was the railroad which unintentionally created a new social sphere of the dispossessed who rode the trains in search of sustenance both physical and intellectual. That dramatic backdrop was one of hopped trains and thumbed rides. Kerouac used his thumb to hitchhike or rode along in trains (he was a brakeman), and (sometimes) in stolen cars courtesy of his muse Neal Cassidy. All this couched in a modern descendant of literature’s great Greek dramas, Japanese Noh dramas, and Ethiopian drama, Partch tells the heroic adventures of his, the generation that followed the “jazz age” and preceded the beat generation much as Kerouac helped evolved literature from the early twentieth century American romanticism of Thomas Wolfe eventually to the “Beat Generation”.

There are six tracks on this release comprising six works. The last “bonus” track is a speculatively realized version suggested but never realized in Partch’s lifetime and it is more than just filler. Like the prior releases, this one speaks to the fans and enthusiasts who seek a complete rendering of every last note the composer wrote.

The Cloud Chamber Bowls, the Chromelodeon, the plectra and percussion instruments, and the characteristic wooden xylophones announce the first work and provide the listener a context in no uncertain terms that this is an expansion of the musician’s harmonic palette. It signifies that performers and audience are now in a very distinctly different world.

The Eight settings that comprise Barstow went through several revisions (1941, 1954, 1968). On this release we are presented with the most recent revisions of the eight inscriptions. The original version of 1941 for voice and guitar is available on the first volume and I believe this is the version that Maestro Schneider performed at an Other Minds concert in San Francisco some years ago.

This present version utilizes a chamber sized ensemble and adds solo and other voices that act like a Greek chorus describing the unfolding drama. If you’ve only heard the version on previous recordings, you’re in for a treat. Both male and female voices are used as appropriate to the gender of the writer of the text. This final version of Barstow here takes on a much grander form, in a larger dramatic splendor which fleshes out, as much as possible, the people (or at least the memories of the people) behind these lonely evanescent texts.

The second and third tracks, clocking in at just over three minutes and just under three minutes respectively are also more elegantly “dressed” with a more elaborate and dramatically effective presentation depicting news headlines (San Francisco) as they once sounded with paper boys hawking their wares and then the text of a letter (The Letter) from one hobo to another, a message to the composer of the work that serve to establish a context. There is some marvelous instrumental music that drives these dramatic segments in a very cinematic, impressionistic manner.

The fourth track, U.S. Highball, in this 1955 revision is a much longer (nearly 30 minutes) description of a train trip which Partch actually traveled. The vocal writing reflects the composer’s mature style and this movement is arguably the heart of this music dramatic foray. The instrumental sections imitate train whistles (with Doppler effects convincingly achieved due to the uniquely non-western tunings). Disembodied voices accompanied by the ever present and imposing musical instruments tell a surreal narrative of a journey as relevant to the ever evolving state of the art that resonates deeply with the feel of the era much as “On the Road” resonated with the esthetic vibe of the following generation. It is essentially brief narratives that are woven into a compelling story and a beautiful example of music drama revisioned to a generational esthetic.

Track five is in effect a sort of humorous postlude. Here, in addition to Partch’s unique instruments, the composer added parts for saxophone and trumpet. These choices were inspired by the composer’s appreciation of the artistry of Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan (with whom he had wished to collaborate). “Ulysses at the Edge” concludes the drama…

But wait…we have an encore. Here, the scholarship and deep respect for Harry Partch’s work gets a sort of little after party of its own here. It is an ingenious version of that same little postlude we just heard with some improvisatory passages driven by a desire to do honor to a collaboration which never occurred…until now.

I refer interested listeners to the very fine liner notes booklet for details on the army of scholars, musicians, and other artists but let me just list the performers:

Erin Barnes, Paul Berkolds, Alison Bjorkedal, Tim Feeney, Dustin Donahue, Aron Kallay, Vicky Ray, John Schneider, Derek Stein, Nick Terry, and Alex Wand played the Partch instruments. Dan Rosenboom played trumpet and Brian Walsh played baritone saxophone.

The instruments heard included:

Diamond Marimba, Spoils of War, Kithara II, Cloud Chamber Bowls, Canon, Bass Marimba, Chromelodeon, and Surrogate Kithara. These may not be sentient but their presence suggests otherwise.