OM 19, the final bow. Left to right: Charles Amirkhanian, Charles Celeste Hutchins, Joseph Byrd, Wendy Reid, Myra Melford, Roscoe Mitchell, John Schott, Mark Applebaum, John Bischoff, Don Buchla

This past Friday and Saturday the San Francisco Jazz Center hosted the 19th annual Other Minds Festival concerts. This is the first year not to feature an international roster. Instead the focus was on composers from northern California. (Strictly speaking these composers’ creative years and present residence is northern California.) It was not a shift in policy but a focus on a less generally well known group of artists who have not enjoyed the exposure of east coast composers but have produced a formidable body of work that deserves at least a fair assessment. In fact these concerts presented a fascinating roster of composers from essentially three generations.

The first generation represented was one which came of age in the fabled 1960s and included electronic music pioneer Don Buchla, AACM founding member Roscoe Mitchell and proto-minimalist Joseph Byrd. The second was represented by Wendy Reid, Myra Melford and John Bischoff. And the youngest generation by Mark Applebaum and Charles Celeste Hutchins.

The program opened on Friday night with a sort of pantomime work by Stanford associate professor of music Mark Applebaum. The piece, called Aphasia (2010) consists of an electronic score to which the composer, seated in a chair, responds with a variety of carefully choreographed gestures. The result was both strange and humorous. The audience was both amused and appreciative.

Applebaum’s Metaphysics of Notation (2008) performed by the Other Minds Ensemble. Left to right: Myra Melford, John Bischoff, Wendy Reid, John Schott, Joseph Byrd, Charles Amirkhanian and Charles Celeste Hutchins

Applebaum’s graphic score Metaphysics of Notation (2008) was projected overhead while the ensemble played their interpretations of that score. The ensemble, dubbed the Other Minds Ensemble, consisted of most of the composers who participated in the festival including Mr. Amirkhanian displaying his facility with a percussion battery among other things. (Presumably Roscoe Mitchell, who was reportedly not feeling well, would have joined the ensemble as well.) Mr. Applebaum was conspicuously absent perhaps so as to not unduly influence the proceedings.

Ribbons strewn across the stage, a part of the Other Minds Ensemble’s interpretation of the Metaphysics of Notation

The piece was full of minimal musical gestures, humorous events like ribbons strewn across the stage and the popping of little party favors that emitted streamers. The ensemble appeared to have a great deal of fun with this essentially indeterminate score which they are instructed to interpret in their own individual ways. It was a rare opportunity to see and hear Mr. Amirkhanian (who is a percussionist by training) as well as an opportunity for the other composer/performers to demonstrate their skills and their apparent affinity for this type of musical performance. Again the audience was both amused and appreciative.

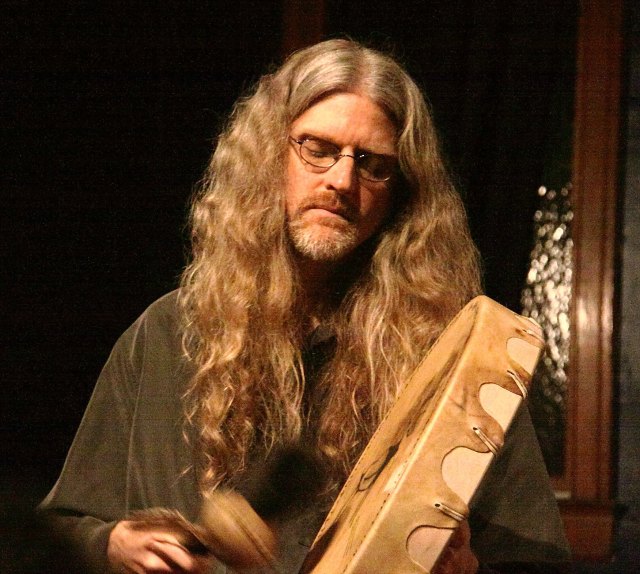

Mark Applebaum performing on his invented instrument.

Projection of Applebaum performing with view of the composer/performer stage right as well.

The third piece by Applebaum featured the composer with his invented instrument and electronics playing on a balcony stage right with a projection of himself on the big screen. He produced a wide variety of sounds from his fanciful computer controlled contraption that seemed to please the audience. This is the kind of unusual genre-breaking events which tend to characterize an Other Minds concert.

The second composer of the night was the elusive Joseph Byrd who is perhaps best known for his cult classic album The American Metaphysical Circus by Joe Byrd and the Field Hippies from 1969. A previous band, The United States of America released a self-titled album which received critical acclaim in 1968. Both are apparently out of print but available through Amazon.

Joe Byrd studied music with Barney Childs and worked with La Monte Young, cellist Charlotte Moorman, Yoko Ono and Jackson Mac Low. Byrd went on to produce a great deal of music by others and also wrote music for films and television but his own compositions have only come to light again recently with the release of a New World CD released in 2013 which presents his work from 1960-63. Mr. Amirkhanian said that it was this disc that got him interested in inviting Byrd to Other Minds (Byrd also taught at the College of the Redwoods in Eureka, California.).

This is the sort of musical archeology for which Other Minds has become known. Amirkhanian is known for his ability to find and bring to performance and recordings music which has been unjustly neglected. Hopefully this appearance will be followed by more releases of Byrd’s other music as well.

Byrd was represented here by performances of Water Music (1963) for percussionist and tape with Alan Zimmerman (who was one of the producers of the New World album) played the spare percussion part which integrated well with the analog electronic tape.

Alan Zimmerman performing Joe Byrd’s Water Music.

A second piece, Animals (1961) was performed by the brilliant and eclectic bay area pianist Sarah Cahill with Alan Zimmerman and Robert Lopez on percussion and the fiercely talented Del Sol String Quartet (Kate Stenberg and Richard Shinozaki, violins, Charlton Lee, viola and Kathryn Bates Williams, cello). This was another piece with soft, mostly gentle musical gestures involving a prepared piano and predominantly percussive use of the string players. It was interesting to contemplate how this long unheard music must have sounded in 1961 but it was clear that it communicated well with the audience on this night.

Animals (1961)

John Bischoff performing his work Audio Combine (2009)

Following intermission we heard two pieces by Mills composer/performer John Bischoff. The first was Audio Combine (2009) which featured Bischoff on this laptop producing a variety of digitally manipulated sounds. It was followed by Surface Effect (2011) with creative lighting effects/animations that nicely complemented the laptop controlled analog circuitry. Bischoff’s music is generally gentle and clear. It belies the complexity of its genesis in state of the art computer composition and performance for which he is so well known.

John Bischoff performing Surace Effect (2011)

All this led to the final performance of the evening by Don Buchla whose modular synthesizers were developed in the early 1960s with input from Ramon Sender, Morton Subotnick, Pauline Oliveros and Terry Riley at the legendary San Francisco Tape Music Center (which later became the Mills Center for Contemporary Music). Buchla also designed the sound system for Ken Kesey’s bus “Furthur” which featured in the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Don Buchla on the Buchla Bos and Nannick Buchla on the piano with film projection performing Drop by Drop (2012) in its American premiere.

The conclusion of Friday’s program consisted of the American premiere of a Drop by drop by Don Buchla for Buchla 200e, electronically controlled “piano bar” (another Buchla invention) and film projection. The film was made in collaboration with bay area film maker Sylvia Matheus. The sequence of images began with a dripping faucet and proceeded to a waterfall and then to emerging pictures of birds all the while accompanied by the various sounds from the synthesizer and the piano.

Nannick and Donald Buchla receiving warm applause from the audience.

The Saturday night performances began with Charles Celeste Hutchins and his laptop improvising system. Hutchins, a San Jose native, describes his system as related to Iannis Xenakis’ UPIC system and utilizes a live graphic interface which the computer uses to trigger sound events.

Charles Celeste Hutchins at his laptop performing Cloud Drawings (2006-9)

The drawings were projected onto the overhead screen. There seemed to be a somewhat indirect correlation between the drawings and the resultant sounds and much of the tension of this performance derived from wondering what sounds would result when the cursor reached that particular drawing object. The audience is basically watching the score as it is being written, a rather unique experience and the Other Minds audience clearly appreciated the uniqueness.

The projected graphic score for Cloud Drawings.

The Actual Trio: John Schott, guitar, Dan Seamans, bass, John Hanes, drums.

John Schott and his Actual Trio then took the stage to perform his own brand of jazz which seemed to be a combination of free jazz, Larry Coryell and perhaps even Jerry Garcia. But these descriptions are merely fleeting impressions and are not intended to detract from some really solid and inspired music making. After the conclusion of the set this listener half expected an encore.

But the program moved on toWendy Reid’s performance as we watched the stage being set up with music stands, some electronic equipment and a parrot in a cage.

Tree Piece #55 “lulu variations” with Tom Dambly, trumpet, Wendy Reid, violin and electronics and Lulu Reid on vocals.

Reid’s Tree Pieces are an ongoing set of compositions incorporating nature sounds with live performance. This is not unlike some of Pauline Oliveros’ work in that it involves careful listening by the musicians who react within defined parameters to these sounds.

Lulu the parrot appeared nervous and did a lot of preening but did appear to respond at times. The musicians responded with spare notes on violin and muted trumpet. It was a whimsical experience which stood in stark contrast to the more declarative music of the previous trio but at least some of the audience, apparently prepared for such contrasts, was appreciative.

Myra Melford performing selections from Life Carries Me This Way (2013)

The diminutive figure of Myra Melford took command of the piano and the hearts of the audience in her rendition of several pieces from her recent CD. She played sometimes forcefully with thunderous forearm cluster chords and sometimes with extreme delicacy but always with rapt attention to her music. Her set received a spontaneous standing ovation from a clearly roused audience. She is a powerful but unpretentious musician who clearly communicates well with her audience.

Roscoe Mitchell, Vinny Golia, Scott Robinson and J.D. Parran following their performance of Noonah (2013)

The finale of OM 19 was the world premiere of an Other Minds commission, the version for four bass saxophones of Roscoe Mitchell’s Noonah (pronounced no nay ah). It is the latest incarnation of a piece of music that Mitchell describes as having taken on a life of its own. It exists now in several different versions from chamber groups to orchestra.

The piece is vintage Roscoe Mitchell, a combination of free jazz and sometimes inscrutable compositional techniques which clearly enthralled the very focused performers. What the piece seemed to lack in immediate emotional impact it made up in mysterious invention which was brought out grandly by the very experienced and committed players.

Mitchell, who was not able to attend on the previous night, appeared rather tired but played with a focus and enthusiasm that matched his fellow musicians. Like all of Mitchell’s music there is a depth and complexity that is not always immediately evident but does come with repeated listenings and performances.

Thus concluded another very successful edition of Other Minds. Now we look forward to the gala 20th anniversary coming up in March, 2015.

37.765206

-122.241636