The amazing Stuart Dempster at a house 2015 house concert at Philip Gelb’s Sound and Savor.

In many ways this has been a year of reckoning. I kept my promise to myself to double down on writing this blog and have already reached more viewers than any previous year. I am now averaging a little more than 1000 hits a month from (at last count) 192 countries and have written 74 pieces (compared to 48 last year). I need to keep this up just to be able to stay in touch with similarly minded folks (thanks to all my readers). Add to that the fact that a piece of music I wrote 15 years ago was tracked down by the enterprising Thorson and Thurber Duo. They will provide me with my very first public performance this coming July in Denmark. Please stop by if you can. After having lost all my scores (since 1975) in a fire and subsequently the rest of my work on a stolen digital hard drive I had pretty much let go of that aspect of my life but now…well, maybe not.

Well one of my tasks (little nudges via email have been steadily coming in) is to create a year end “best of” list. Keep in mind that my personal list is tempered by the fact that I have a day job which at times impinges on my ability to do much else such as my ability to attend concerts. However I am pleased to say that I did get to 2 of the three Other Minds concerts this past year. The first one featured all the music for string quartet and string trio by Ivan Wyschnegradsky (1893-1979). The second one featured music by the same composer written for four pianos (with two tuned a quarter tone down). Both of these concerts exceeded my expectations and brought to light an amazing cache of music which really deserves a wider audience. These are major musical highlights for this listener this year.

The Arditti Quartet acknowledging the applause at the Wyschnegradsky Concert.

Read the blog reviews for details but I must say that Other Minds continues to be a artistic and musical treasure. Under the leadership of composer/producer/broadcaster Charles Amirkhanian (who turns 75 in January) the organization is about to produce their 25th anniversary concert with a 4 day series beginning in April, 2020. For my money its one of the reasons to be in the Bay Area if you love new music. He is scheduled for a live interview on the actual day of his birthday, January 19th as a guest on his own series, The Nature of Music. This series of live interviews (sometimes with performance material) with composers and sound artists he has hosted since 2016.

Amirkhanian performing at OM 23 (2018)

Next I will share with you my most obvious metric, how many views my various blog posts got. I have decided to share all those which received more than 100 views.

The winner for 2019 is:

Linda Twine (unknown copyright)

Linda Twine, a Musician You Should Know

A rather brief post written and published in February, 2018 for Black History Month. It was entirely based on internet research and it got 59 views that year. As of this writing in 2019 it has been seen 592 times. I have no idea why this “went viral” as they say. I just hope it serves only to her benefit. Amazing musician.

Fatu Duo

Charming little album of lesser known romantic violin and piano pieces played by a husband and wife duo. This self produced album seems to have had little distribution but for some reason people are enjoying reading about it. I only hope that the exposure will boost their sales. This is a fun album.

G. Thomas Allen

Darryl Taylor

John Holiday

The Three Black Countertenors

I’m guessing this is one of my “viral” posts. I wrote it in 2014 and it continues to get escalating hits, 180 this year. The title pretty much says it all. First time three black countertenors appeared on the same stage.

Jenny Q Chai

This concert was an all too brief presentation of some very interesting work. Quite a pianist too. File this artist’s name in your “pay attention” category.

Heavenly Violin and Piano Music by Giya Kancheli

Giya Kancheli (1935-2019), one of the artists we lost this year (I refuse to do that list). If you don’t know his work you should. He wrote I think 7 Symphonies and various concertos, film scores, and other works. He was sort of elected to the “Holy Minimalists” category but that only describes a portion of the man’s work. Very pretty album actually.

Because Isaac Schankler

This composer new to me, works with electronics, and maintains an entertaining presence on Twitter. Frankly, I’m not sure exactly what to make of this music except to say I keep coming back to it. Very leading edge material.

Wolfgang von Schweinitz’s “Klang”

A very different music from that of Schankler listed just above. But another recording to which I find myself returning. Thanks to Mr. Eamonn Quinn for turning me on to this one.

A New Voice for the Accordion

I pretty sure that Gene Pritsker can shoulder at least part of the blame for connecting me with this great new musician The accordion has come a long way and this guy leads it gently forward.

Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety in a new recording

Loved this one. I had only listened to this work three or four times and probably not with adequate attention. Hearing this performance was revelatory. It’s a great work deserving of a place in the standard repertoire/

Charles Dean Dixon (1915-1976)

Carl Van Vechten’s 1961 portrait of Marilyn Horne with her husband Henry Lewis.

Thomas Wilkins (1956- )

Michael Morgan (1957- )

Paul Freeman

James Anderson De Preist (1936-2013)

Black Classical Conductors

Written in 2013, just an occasional piece about black conductors for Black History Month. It’s now been read over 2000 times. It is my most read article. It’s embarrassingly incomplete and in need of a great deal of recent history but that’s a whole ‘nother project.

Blue Violet Records

Blue Violet Duo

So glad this disc got a little exposure. Its gorgeous. This disc of jazz influenced classical Americana unearths some real musical gems.

Shakuhachi Ecstasy

OK, I meet this guy at a vegan underground restaurant (whose proprietor is noted Shakuhachi player, Philip Gelb). A little casual conversation, a few vegan courses (Phil can seriously cook), and whaddya know? About a month or so later he sends me this gorgeous self produced set of him playing shakuhachi…but the upshot is that this is the distillation of the artist’s sensibilities filtering his very personal take on the world via his instrument. It has collectible written all over it and that is as much due to the music itself as to the integrated graphics and packaging. You really have to see and hear this trilogy. It got over 100 hits. Thanks to Cornelius Boots and Philip Gelb (musical and culinary concierge).

That’s it. Everything else (300 plus articles total with 74 from this year) got less than 100 views.

Personal Favorites

It was a great year for recordings and I listened to more than I did last year. Some may have noticed some experimentation with writing style and length of review here. The problem is that the very nature of my interest is the new and unknown so I have to do the research and have to share at least some of that to hopefully provide some context to potential consumers that will ignite the idea, “gotta check that out” without then boring them to death.

For this last section I will provide the reader with a list in reverse order of the publication of my reviews of CD and streaming releases that prompt this listener to seek out another listen and hopefully draw birds of a feather to listen as well.

Keep yer ears peeled. This young accordion virtuoso is an artist to watch. This was also one of my most read review articles. This guy is making the future of the instrument. Stay tuned.

This artist continues to draw my attention in wonderful ways. Her scope of repertoire ranges hundreds of years and she brings heretofore unknown or lesser known gems to a grateful listening audience. Blues Dialogues is a fine example. It is also reflective of the larger vision of the Chicago based Cedille label.

I found myself really taken by this solo debut album by American Contemporary Ensemble (ACME) director Clarice Jensen. In particular her collaboration with La Monte Young student Michael Harrison puts this solo cello (with electronics) debut in a class all its own, This independent release is worth your time.

This album of string chamber music arrangements of Mahler is utterly charming. No Time for Chamber Music is a seriously conceived and played homage.

Canadian composer Frank Horvat’s major string quartet opus is a modern classic of political classical music. It is a tribute to 35 Thai activists who lost their lives in the execution of their work. His method of translating their names into a purely musical language has created a haunting and beautiful musical work which is a monument to human rights.

Donut Robot is a playful but seriously executed album. The kitschy cover art belies a really entertaining set of short pieces commissioned for this duet of saxophone and bassoon. Really wonderful album.

It has been my contention that anything released on the Starkland label requires the intelligent listener’s attention. This release is a fine example which supports that contention. Unlike most such releases this one was performed and recorded in Lithuania by the composer. Leave it to the new music bloodhound, producer Tom Steenland to find it. In Search of Lost Beauty is a major new work by a composer who deserves our attention.

My favorite big label release. This new Cello Concerto from conductor/composer Esa-Peka Salonen restores my faith that all the great music has been written and that all new music is only getting attention from independent labels. Granted, Sony is mostly mainstream and “safe” but banking on the superstar talent of soloist Yo-Yo Ma they have done great service to new music with this release. Not easy listening but deeply substantive.

This release typifies the best of Chicago based Cedille records’ vision. Under the guidance of producer James Ginsburg, this local label blazes important paths in the documentation of great music. “W” is a disc of classical orchestra pieces written by women and conducted by the newly appointed woman conductor, Mei-Ann Chen. She succeeds the late great Paul Freeman who founded Chicago’s great “second orchestra”, the Chicago Sinfonietta. Ginsburg taps into Chicago’s progressive political spirit (I guess its still there) to promote quality music, far beyond the old philosophy of “dead white men” as the only acceptable arbiters of culture. Bravo to Mr Ginsburg who launched Cedille Records 30 years ago while he was a student at the University of Chicago.

Become Desert will forever be in my memory as the disc that finally got me hooked on John Luther Adams. Yes, I had been aware of his work and even purchased and listened to albums like Dream in White on White and Songbirdsongs. I heard the broadcast of the premiere of the Pulitzer Prize winning Become Ocean. I liked his music, but this recording was a quantum change experience that leads me to seek out (eventually) pretty much anything he has done. Gorgeous music beautifully performed and recorded.

OK, I’m a sucker for political classical. But Freedom and Faith just does such a great job of advancing progressive political ideas in both social and musical ways. This is a clever reimagining of the performance possibilities of the string quartet and a showcase for music in support of progressive political ideas.

Michala Petri is the reigning virtuoso on the recorder. Combine that with the always substantial production chops of Lars Hannibal and American Recorder Concertos becomes a landmark recording. Very listenable and substantive music.

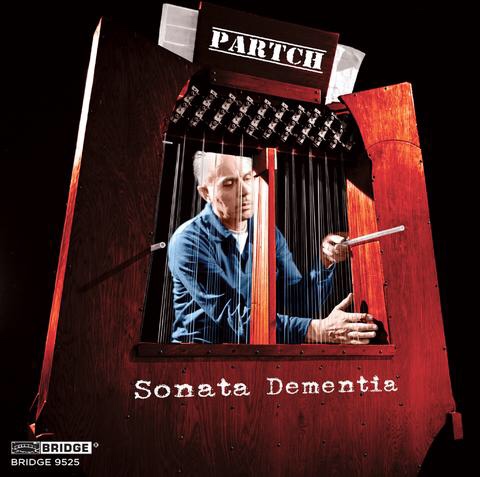

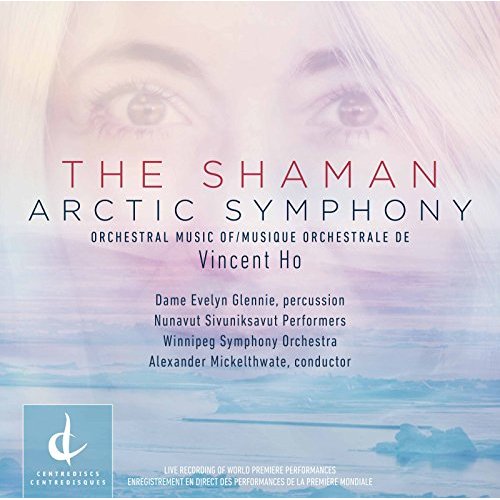

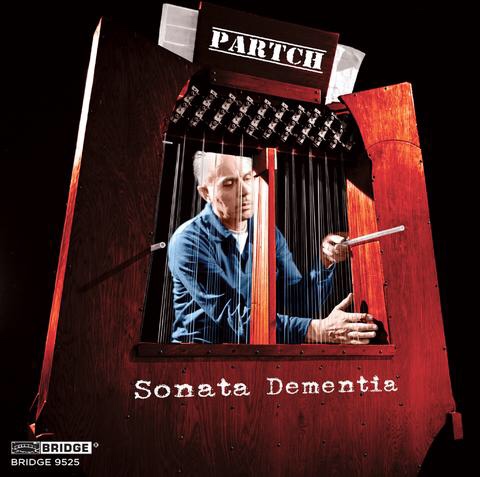

I have admired and sought the music of Harry Partch since I first heard that excerpt from Castor and Pollux on the little 7 inch promotional LP that came packaged with my copy of Switched on Bach. Now this third volume in the encyclopedic survey of the composer’s work on Bridge Records not only documents but updates, clarifies and, in this case, unearths a previously unknown work by the master. Sonata Dementia is a profoundly important entry into the late composer’s discography. I owe PARTCH director, the composer/guitarist John Schneider a sort of apology. I had the pleasure of interviewing him about this album and the planned future recordings of Partch’s music but that has not yet been completed. You will see it in 2020 well before the elections.

The aforementioned

Shakuhachi Trilogy is a revelatory collection which continues to occupy my thoughts and my CD player.

Gil Rose, David Krakauer, klezmer and the inventive compositional talent of Mathew Rosenblum have made this album a personal favorite. Lament/Witches Sabbath is a must hear album.

Another Cedille disc makes the cut here, Souvenirs of Spain and Italy. The only actual Chicago connection is that the fine Pacifica Quartet had been in residence at the University of Chicago. But what a fine disc this is! The musicianship and scholarship are astounding. Guitar soloist Sharon Isbin celebrates the 30th anniversary of her founding the department of guitar studies at Julliard, a feat that stands in parallel with the 30th anniversary of the founding of Cedille records. This great disc resurrects a major chamber work by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and presents a definitive program of chamber music for guitar and string quartet. This one has Grammy written all over it.

This New Focus recording was my personal introduction to the music of Du Yun and I’m still reeling. What substance! What force! Dinosaur Scar is quite an experience.

Another Starkland release, this album of music by the great new music pianist is a personal vision of the pianist and the creators of this forward looking repertoire. Eye to Ivory is a release containing music by several composers and championed most ably by Kathleen Supové.

Chicago born Jennifer Koh is one of the finest and most forward looking performers working today. Limitless is a collaboration between a curious but fascinating bunch of composers who have written music that demands and receives serious collaboration from this open minded ambassador for good music no matter how new it is. And Cedille scores another must hear.

Many recordings remain to be reviewed and some will bleed over into the new year so don’t imagine for a second that this list is comprehensive. It is just a personal list I wished to share. Happy listening and reading to all.